Chapter V. Early Tudor Gardens

Description

This section is from the book "A History Of Gardening In England", by Alicia Amherst. Also available from Amazon: A History Of Gardening In England.

Chapter V. Early Tudor Gardens

" Sure gates, sweete gardens, stately galleries Wrought with faire pillovves and fine imageries ; All those (O pitie !) now are turned to dust And overgrowne with black oblivious rust".

Spenser, Ruins of Time.

TOWARDS the end of the fifteenth century fresh influences were brought to bear on the national life, and numerous changes set in. The marriage of Edward the Fourth's sister with the Duke of Burgundy, and through that alliance the increased intercourse with Flanders, led to many alterations in social life. The comparative peace which followed the termination of the Wars of the Roses encouraged a new style of domestic architecture, and comfortable red brick houses succeeded the old castles. The gardens were no longer of necessity confined within the embattled castle walls. The houses in the new style were not built on the tops of hills, but usually on lower lying ground, and were surrounded by a moat. There was some little space within the moat devoted to a garden, or a few plants were placed in the courtyard. The prolonged peace diminished the necessity of keeping all property within the protecting lines of the moat, and thus the custom came in of having gardens beyond it. With this additional space—for there was frequently more room inside the moat than there had been within castle walls, even if the garden were not made outside—there was more scope for play of fancy, and before long several changes in design came in.

One of the first innovations was the railed bed—flower-beds a both sides bearing up the rails in the said garden at 12d. the piece, £4. 16s.— Also paid to the same for like painting of 960 yards in length of rail in the said garden with white and green, and in oil, price the yard 6d., £24." *

Railed flower bed, from french ms. of the roman de la rose. c I45O. bm. egerton 2022.

These items are repeated with variations; the posts and rails were painted " white and green in antyke oiled colours," and " flat posts " occur in the place of " flat povvnchens".

Another novelty introduced in the first years of the Tudor period, and soon a conspicuous feature in all gardens, was topiary enclosed by low fences of trellis-work. These trellis railings came into fashion just before Tudor times, but they remained in vogue for many years. When, in 1533, Henry VIII. made great alterations in the gardens of Hampton Court, flower-beds of oblong form were made in the King's new garden. They were surrounded by rails painted green and white—the Tudor colours —as may be seen in the original picture of Henry VIII., from which the illustration on page 89 is taken. In the Hampton Court expenses, 1533, numerous entries refer to the purchase of these rails.

* Exchequer, Treasury of Receipt, Miscellaneous Books, No. 237. This is a large book of Expenses at Hampton Court, 24th Henry VIII.

" Paid to [Henry Blankeston, of London, painter] for the like painting of 96 flat pownchens with white and green, and in oil, wrought with antyke work, "opus topiarum," that is to say, quaintly cut trees and shrubs. This art, although new in England, was of very ancient origin, having been known to the Romans. But it is not until this date that it is mentioned as being practised in England. The new idea found great favour in this country, and much time and trouble were expended in producing these monsters in trees, and the taste remained in fashion for more than two centuries. Leland, in his Itinerary, in the early years of the sixteenth century, mentions a place where striking specimens of the work might be seen ; " at Uskelle village, about a mile from Tewton, is a goodly orchard with walks opere topiario and at " Wresehill Castle" he also describes an orchard with " mounts opere topiario writhen about in degrees like turnings of cokilshells to come to the top without payne." This leads me to speak of yet another peculiarity which was much developed about this time, the "mount," like this one at Wressel Castle, where Leland saw the cut trees. In the thirteenth century there were made in some of the monasteries " mounds" of earth against the garden-walls, to enable the inmates to peer over them into the outer world. During the following centuries, "mounds" or "mounts," of simple construction, were frequently to be found in the gardens, but in Tudor times, the "mount" became a much more important accessory than formerly. They were usually made of earth covered with fruit or other trees. Mounts were generally thrown up in "divers corners" of the orchard, and were ascended by "stairs of precious workmanship," or a spiral path planted on either side with shrubs, cut in quaint shapes, or with sweet-smelling herbs and flowers. At Rockingham, there remains a specimen of one form of mount. A great terraced-mound of earth, covered with turf and a few trees, is raised against a part of the high wall which surrounds the garden and behind which the keep formerly stood.

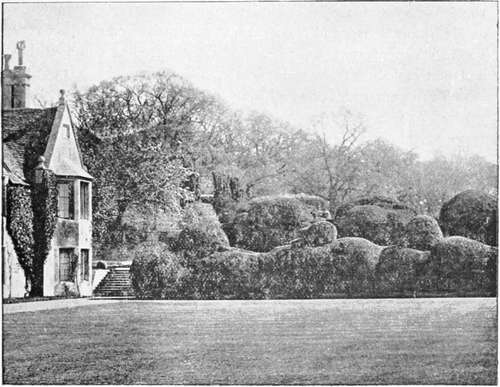

The mount, rockingham.

Old yew walk and mount rockingham.

From the top of this the eye ranges across the garden with quaintly cut yew-trees, over a magnificent view of the open country beyond; thus the mount served in early times as a "look out" or watch tower. If the garden or orchard happened to be situated in a park, and herds of deer browsed close to its walls, the mount then became useful as a point from which one " myghte shoot a bucke." * The top of the mount was often surmounted by an arbour, either of trellis-work and creepers, or a more substantial building. Probably the finest specimen of this kind of ornament was the " mount ' at Hampton Court, and from various sources we can form a very good idea of what it was like. It was situated at the southern end of the " King's New Garden," which was made in 1533, at which time a gardener named Edward Gryffyn superintended the work. The mount was made on a brick foundation, as there were payments made to " John Dallen of London, bricklayer," for " laying of 256,000 of brick upon the walls about the new garden, betwixt the King's lodgings and Thames, and the foundations of the mount standing by Thames, taking for every 1000 14d., by convention £14. 18s. 8d." The earth was then raised and planted with quicksets. The sum of 54s. 8d. was paid to Lawrence Vyncent and John Gaddisby of Kyngston, for four loads of quicksets, every load containing thirty hundred sets of them " to set about the mount by the King's new garden." Another entry refers to the purchase of " ash poles to make rails to bind the quicksets," and " two bundles of wylly roddes to bind " them; and " three pear trees to set in the mount." The most elaborate part of the mount was the arbour. The " South arbour" seems to have been the one on the mount, but mention is also made in the accounts of a west arbour, which was apparently very similar, as the same things were bought for both, and payment made to " Iohn a gwylder smith " " for 300 of broddes serving for the fretts in the roof of the south herber at the mount I2d. the 100, 3s.," and to Galyon Hone, the King's glazier, several sums were paid, of which the following is a sample. " Item in the mount in the garden 48 lights, every light in the upper story containing 4 1/2 foot, in the nether story every light containing 4 1/2 foot 3 inches, which amount in all (to) 211 foot at 3d. the foot, £4. 7s. 11d." This gives one some idea of how large the arbour was, and how carefully it was made. It appears, furthermore, from the accounts, that the "south herber" was connected with the west one by a gallery running along the wall, which was made of wooden poles and trellis-work. Such galleries were marked characteristics of late fifteenth and early sixteenth century gardens and designs for them are found in some old works; the best of these being in the Hortus Floridus of Crispin de Pas (or Passe) which was translated into English in 1615. They existed in Hampton Court before Henry VIII. made his alterations there, and are thus referred to in Cavendish's metrical life of Wolsey.

* Lawson, New Orchard.

Garden with a gallery, from " the second booke of flowers, FRU1CTS, beastes, birds, and flies," 1650.

Continue to: