Memories Of Big Game Hunting. Part 9

Description

This section is from the book "Wild Life In Central Africa", by Denis D. Lyell. Also available from Amazon: Wild Life in Central Africa.

Memories Of Big Game Hunting. Part 9

The oldest animal measured 55m. at the shoulder, and he had rather an abnormal head, for the horns were extremely thick and cobby, though they only measured about 33m. in the curve. This was not a young sable, but a very old beast, with large bulges on the base of his horns. Only fully adult animals have these bulges. As his body measurements were very large, I came back next day and took his complete skin for setting up. Most of the meat of the other animal was carried to camp and eaten up that night by my hungry men.

On the 25th I wounded a bull sable with a very pretty pair of horns, but lost him. After getting back to camp and having some food and a rest, I decided to go back in the afternoon and have another look for him. Going through some thick grass I found a good blood spoor, and followed it, when suddenly, within fifty yards, up jumped the bull, and I hit him hard somewhere in his stern. Going on, I put him up again, as I thought, and fired and dropped him with a shot in the spine. On going up to him I found that this was quite another animal, as he had no previous wound in his body, and I noticed the head was different, although it was quite a good one.

After searching around, one of the men found the blood of the first one, and I soon came on him lying down; but, when he saw us, he was quickly on his feet. However, he waited just a little too long, for I got the sights on his shoulder and killed him where he was standing. This was a most beautiful animal, being very slenderly formed in comparison to the one I had shot on the 23rd. His horns also were much longer and thinner, as they measured nearly 40 inches on the curve, and had very even, sharp points. I took his complete skin, and it can, probably, now be seen in the Transvaal Government Museum in Pretoria, to which institution I sent it.

On the 27th I went out to try to find eland, and came on the fresh spoor of a large herd which I spoored up. Eland are easy beasts to track, as being such heavy animals they leave a good print. When I first saw them they were all grouped together, and in the thick grass and bush in which they were standing I found it most difficult to see the best head.

I got on them with the glasses, and at last saw a fine big bull, so I took a steady shot and the bullet, a solid, went right through him, and raised the dust far on the other side. As he went off I fired two more shots, and hit with one at least.

I could see one of his hind legs dangling, so I knew I would get him, as a heavy beast can never go far with a broken back leg. Before I finished him I took two photographs of him moving in front of me, and then gave him a bullet in the heart, which quickly killed him.

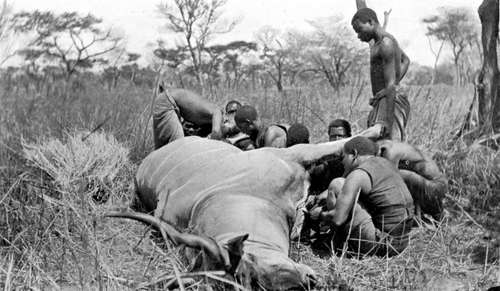

Eland Bull Being Skinned For Preservation (Horns 29½in., straight.)

Some natives hearing the shots came running up, so I asked them to go and get some water for my men and myself from the stream near their village. One man also brought me back a few eggs in a small pot, which I boiled and enjoyed.

Wanting the complete skin of this animal for setting up, I took many measurements, but as I have given some of them in Chapter III., I will only say that he was 72½in. in height, and his horns measured 29½in., and were nicely shaped. It took over three hours in the hot sun to get his hide off, and I was very tired and thirsty before I reached camp at sundown that evening; but a warm bath and a good dinner soon freshens a man up. I used to have a big camp fire every evening, and my happiness would have been complete if I had only had a congenial companion to talk to.

The next few days were cloudy, a few showers of drizzling rain came on at times, and I had the greatest difficulty in getting the eland skin dried. In such weather the thick neck skin will not dry, and in most cases it has to be thinned down with knives so as to hasten the drying. As I could not get my knives sharp enough I used a pair of good ivory-handled razors, which improved the skin, but not the razors.

Although I took a great deal of trouble over it, this skin eventually went bad on its way to the Transvaal, as, owing to the carelessness of a firm of Portuguese forwarding agents at Lourenco Marques, it was delayed in transit. Truly, collecting in a country like this is disappointing work, as after all one's trouble the results are liable to be spoilt by other people's negligence. Freight is very high there for all such heavy packages.

Chiromo district would be a very good one for any collector to work in, as there he would be near the river, where specimens could be placed on the steamers at once for transporting to Chinde. It is a difficult matter getting large skins carried safely through the bush, as they are very apt to be chafed by the thorns, rough trees, and bushes, but I managed this by covering up the ears and head with old sacking and newspapers.

I spent some days trying to get hold of a good bull kudu, as there were several herds in the vicinity of Mausi Hill. On one occasion I wounded a fine fellow with a quick snapshot, but he escaped me, although I spent a long time trying to find him. Another day I managed to stalk a very wary herd and I saw the horns of a bull, but owing to the position he held his head I could not tell whether they were big or not. The shot I fired killed him and I was disgusted to find that his head was a poor one, so I simply took the headskin, and sent it and the skull to the Transvaal Museum, as I thought it might prove interesting to students of natural history to exemplify the formation of growth.

To show how a collector may be robbed of his spoils I shot a nice bull kudu when on a short trip to the Palombe stream, and he had a very pretty head. It was almost sundown when I got him and camp was a good three miles off, near the stream, which was clear running and pure. 1 managed by the help of two big fires to get his skin off up to the neck, so I cut it off there and rolled it up in a bundle and got home by 9 p.m., giving my legs some nasty bumps when getting through the thorny bush by dull moonlight. After cleaning my rifle and eating a good dinner, I went to bed, seeing that the skin was put up in the fork of a large tree beyond the reach of any prowling hyaena that might pay the camp a visit. Next morning I tackled the skin of the head, with the help of a Yao boy named Marki, whom I had taught to skin well. My cook then told me breakfast was ready, so I left Marki to go on with it for the part he was busy on was easy, as the ears had not yet been reached. When I was at breakfast Marki appeared and said in a plaintive voice that he had cut the skin of the neck, and on going over I found he had made a big gash right through it, which quite spoilt it for the purpose of setting up. His error cost me a very nice specimen and a considerable sum of money, so I told him he would be fined.

Kudu Bull Shot In Nyasaland

Continue to:

- prev: Memories Of Big Game Hunting. Part 8

- Table of Contents

- next: Memories Of Big Game Hunting. Part 10