Verba Sesquipedalia

Description

This section is from the book "Smoked Glass", by Orpheus C. Kerr. Also available from Amazon: Smoked Glass.

Verba Sesquipedalia

" A few words by way of introduction," - as an author frequently remarks, with much native ease of manner, when about to astonish such weak-minded readers as peruse prefaces, with some pages of strictly moral information.

Instruction as to the finely subtle significance of certain passages in the appended work, which but for such explanation might seem to have no particular meaning at all, is, of course, the apparent purpose of those few words; but, in a majority of cases, it is their genuine intent to hint, very clearly, that the author of the book should not be ignominiously forgotten in the book itself, and that he takes this opportunity to step casually before the curtain of Chapter I., and be modestly surprised at the ensuing applause.

Having devised the sinister plan of inserting his signature a full score of times in the historical volume which is herewith submitted to the public at a remarkably low price, the present writer may forego the solemnity of such sentences as, " The more thoughtful reader scarcely need be told that the following pages have a deeper," etc. " Something beyond the mere frivolous amusement of an idle hour is intended by," etc. He may also venture to stop addressing "the reader" in terms (inasmuch as that poor-spirited title applies as well to editors, studious inmates of charitable institutions, and other persons, who never pay for books, as to the really solvent individual who patronizes the bookseller), and inscribe what he has here in store to the honest retail book-buyer.

As the honest retail book-buyer now scanning this page has, presumedly, committed himself beyond all redemption by paying for the volume beforehand, it is scarcely worth while to treat even him with any particular ceremony ; and if the absence of any farther propitiatory phrases should happen to strike him as a sign of disrespect, he is hereby coldly authorized to get back his money - if he can. Nothing being certain in this world, however, and the failure of a high-handed outrage of the latter kind coming within the range of human possibilities, it is to be hoped, for the sake of his family, that he will not make a fool of himself in the event of ill success, but quietly submit to the inevitable and go on with his reading. He has the book, the bookseller will not take it back again; and if his bad temper thereat must have some vent, let him seize the first opportunity to recommend a similar purchase to his mother-in-law.

Not to trifle with the miserable man any longer, and supposing his possession of any intelligence whatever to be purely a matter of vague conjecture, let it be explained for his instruction, that when his superiors wish to behold an Eclipse of the Sun, or any other solar entertainment, without injury to their eyes, they use Glass which has been Smoked; and that this sensible medium of astronomical vision not only protects the human sight from harmful confusion of objects, but also presents to it the celestial luminary freed from all extraneous glare and rigidly reduced to his true proportions. Viewed through such a medium, the gorgeous, blazing sun, undergoing eclipse, looks lamentably like an apothecary's most lurid show-bottle suffering serious encroachment from a dinner-pot, and the revelation is calculated to impress feeble minds with the conviction that all is not sun that glitters. Taking his idea from the device and its popular effects, the author of the present volume has, for seven years past, studied a variety of our most dazzling national achievements through a piece of Smoked Glass, with results not less actually strengthening to the eye than astonishingly lessening to the brilliance and apparent magnitude of the military and political pageants surveyed. The ingenuous mind becomes positively confounded at the singularly minute proportions to which much of the most brilliant generalship, patriotism, and statemanship is reduced, when thus stripped of the refractions of partisan prejudice and journalism, and commended in its simple realities to the undazzled sight. To such pitifully small objects, indeed, are they often resolved by the process, that a record of them in relatively diminished terms might fail to make them visible at all; and, hence, to render them clearly perceptible to others, the recorder is compelled to magnify, or, as the critical cant goes, exaggerate them.

So far as Burlesque means Perversion or Distortion of facts, the pages of this book do not come properly under that name. The flaw in the iron of the boiler which holds the really great peril of future explosion is that which the magnifying glass only can detect; and the flaws in Patriotism and Statesmanship, which most seriously menace the stability of a nation, must be magnified (or exaggerated, if you will) to the capacity of popular vision, in order that they may be recognized in time. The writer has precipitated brilliant events and personalities, in Washington and in the South, through a carefully prepared piece of Smoked Glass, and then magnified the reduced precipitates only so much as was requisite to make their organic characteristics patent to the weakest sight. Thus, the pageant of Impeachment is truly given as the culmi-native scene of a feud between Representative Thaddeus Stevens and President Andrew Johnson; the able and dexterous Opening Argument of Manager B. F. Butler is presented in its absolute meaning, rather than in its ostensible design; the pomp of the presiding Chief Justice is shown to have been coldly tolerated, rather than in any sense practically respected; the passiveness of the nation is shorn of its philosophical lustre and explained in its true significance; the patriotic vehemence of partisan journalism of to-day is set forth as it will be judged to-morrow; and the lame conclusion of the drama is attributed to a cause at least as credible and apparently logical as the one generally assigned for it. The same fidelity to concrete actuality may be asserted for the sketches of such representative sectional characters as Captain Villiam Brown, from cosmopolitan New York; the conservative, from Kentucky; the solid Boston man; the loyal Southern Munchausen, etc.; and if, in treating of the concentrative national life at Washington, the author has not felt at liberty to ignore the notorious local coloring which sometimes comes in bottles, he has, at least, involved it in a tenderness of phraseology which should not offend the most decorous.

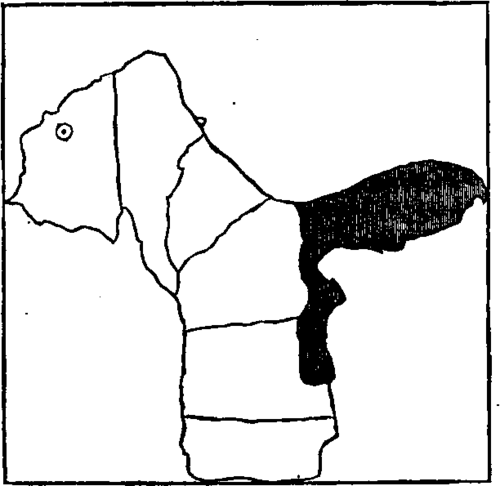

Recalling the honest retail book-buyer to the stand, and once more sneering at his palpable stupidity in requiring so much prefatory explanation, it may be hinted, that the description of Reconstructional life in the Southern comic States, is intended as a logical sequel to the first half of the history. When not beheld through a piece of Smoked Glass, the South has hitherto presented an effulgence of lordly state and chivalry which few dreamed of attributing to the inordinate reflection and refraction of female novelists and heavy mortgages. Even before the rebellion, a well-smoked glass would have enabled the thoughtful observer to trace much over-dazzling to the latter; but now, the same medium diminishes, a race of haughty cavaliers to a community of woefully attired impecuniaires, and reveals their growing eclipse by empty dinner-pots under the delays of Reconstruction. Only the other day, the writer received from a person signing himself " Lucius Natura " a curious anatomical drawing, of which the following is a fac-simile: -

Accompanying which was a letter, wherein Lucius declared that a friend, in Georgia, had sent him from that State the fossil remain indicated by the shaded part of the drawing, and that, from thence, he (Lucius) had, by zoological induction, supplied other portions of the extinct animal. "My immediate impression," wrote Lucius, "was that the fossil (dug up in the extreme South, by-the-by) was nothing more than the hinder portions of some enormous dog (Genus-Caninus tremendibus - Linnaeus), which is represented by the symbol K. I. - a fallacy. I next assigned it to the Beaver tribe (Genus - Tilelus - Buffon; or Plugus- Descartes; or, perhaps, Nobus Coveroe.) By unmistakable indications, I perceived that the animal was assimilated to the lowest rodents, which, says Cuvier, are possessed of the least intelligence of all.

"Goldsmith says: ' The beaver seems to be now the only remaining monument of brutal society. From the results of its labors, which are still to be seen in the remote parts of America, we learn how far instinct can be aided by imitation. We from thence perceive to what degree animals, without .... reason, can concur for their mutual advantage.....When alone, the beaver has but little industry, .... and is without cunning sufficient to guard it against the most obvious and bungling snares laid for it'.

"In short, I am sure that my construction of the animal is correct, and that it belongs to the beaver tribe".

The present historian was much pleased with this triumph of the naturalist, and particularly admired the mild eye of the restored animal; but happening to think of his Smoked Glass, he quickly brought that to bear upon the drawing, and was astounded to discover that the reconstructed fossil was nothing more than a Map of Virginia, the Carolinas, Georgia, Florida, Alabama, and Mississippi, taken apart from the rest of the country and turned on end; and that the mild eye merely indicated the capitol of the first-named State.

From this, it will be perceived, that the Southern comic States have no protection from outrage, while Reconstruction, from whatever cause, is delayed. As the writer knows, from recent personal observation, through a proper medium, at Chipmunk Court House, they yearn eagerly for peace, and the withdrawal of our military vandals; they desire early investments of Northern Capital with them on good bond and mortgage; and, now that the fiercest gust of passion is over, the more advanced of them would even prefer the supremacy of the African, to being ruled, like us of the North, by the Corkasian.

O.C.K.

Continue to: