II. Movements Of The Empty Stomach In Man. Continued

Description

This section is from the book "The Control Of Hunger In Health And Disease", by Anton Julius Carlson. Also available from Amazon: The Control of Hunger in Health and Disease.

II. Movements Of The Empty Stomach In Man. Continued

This ending of the contraction period in an incomplete tetanus appears to be characteristic of young and vigorous individuals. In older people the period usually ends in a single vigorous contraction without tetanus, except under certain conditions. The ending in tetanus appears to be an evidence of relatively great tonicity of the stomach. In one perfectly normal man (Mr. O.) on whom hundreds of observations were made, the entire period (15 to 20 minutes) was virtually a nearly complete gastric tetany.

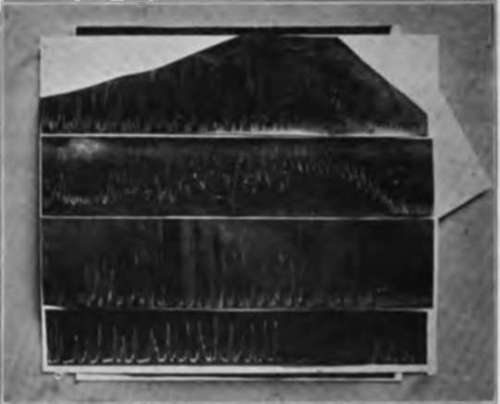

The duration of each contraction varies from 20 to 30 seconds. The contraction time is shortest at the final stage of greatest activity. When the contrary appears to be the case, the tracings show that the prolonged curve is a fusion of two or more contractions. The interval between the contractions varies from 2 to 5 minutes at the beginning of a period to nothing at the end. The duration of the period varies from £ to i§ hours. The usual run is 30 to 45 minutes, the longer periods being exceptional, when there is no experimental interference with the stomach. The number of individual contractions in a period varies from 20 to 70. The period of relative motor quiescence of the empty stomach between the contraction periods varies from 1/2 to 1 1/2 hours in normal adult persons. A few characteristic records of these strong periods of motor activity of the empty stomach in normal persons are shown in Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.-The three upper tracings are typical records of the gastric hunger contractions of normal adult persons toward the end of a hunger period. The tracings arc recorded and arc to be read from left to right, and in each case the gastric hunger contractions cease sentancously near the right end of the tracings. The more rapid excursions arc due to the movements of respiration. The iwttnm tracing shows typical . gastric hunger contractions of a normal dog.

There remains to be noted a rather atypical form of activity of the empty stomach occasionally observed. This consists in contractions, feeble or powerful, that do not fall into distinct groups or periods. These contractions are usually irregular both in strength and in rate. The average rate is slow, the interval between the contractions varying from 5 to 10 minutes. Similar solitary contractions may also appear in the interval between two typical periods of rhythm. These contractions may come two or three in sequence, typical of the beginning of an activity period, but instead of a gradually increasing activity the stomach relapses into relative quiescence for another 10 to 30 minutes.

The reader may question the accuracy of denoting these contractions as motor activities of the empty stomach. In all of these cases the stomach was certainly empty of food. But may not the distended balloon act as food, so far as the food acts mechanically in the way of producing stomach movements? This is, indeed, claimed to be the case by Mangold for the muscle stomach of the buzzard. It is not difficult to prove that certain forms of mechanical stimulation, such as the sudden distension of a rubber balloon in the gastric cavity, may cause brief contractions in the stomach, but it can be shown just as conclusively that the stomach rhythms described above are not caused by the presence of the foreign objeqts in the stomach.

1. The presence of the distended balloon in the stomach between the contraction periods does not induce these contractions.

2. In Mr. V. the gastric contractions can be observed directly through the large fistula without any balloon in the stomach.

3. The contraction periods come on just as frequently without any balloon in the stomach and produce the same effect on consciousness (hunger).

4. In pigeons the periodic strong contractions of the empty crop can be seen directly through the skin and a balloon in the crop does not alter their frequency or intensity.

The Stomach Pulse

When the empty stomach is moderately contracted, direct inspection by the aid of a small electric bulb in the gastric cavity shows distinct oscillations of the rugae synchronous with the arterial pulse. The oscillations of the rugae cause similar oscillations of the gastric juice (mixed with mucin), which is always present in the otherwise empty stomach. When the strong contractions (30-seconds rhythm) appear, the pulse oscillations of the rugae seem to disappear, either because of the greater rigidity of the stomach folds, or else owing to the difficulty of distinguishing the pulse oscillations when the rugae are closely packed and slide rapidly over and past one another, as they do when the fundus contracts. The picture revealed by the gastric cavity when the empty stomach is in a period of rhythmic contractions is interesting, but rather bewildering, and we have ceased to wonder how Beaumont could have so completely failed to grasp the character of the stomach movements in digestion, as he relied mainly on such direct inspection of the stomach of Alexis St. Martin.

Continue to:

- prev: II. Movements Of The Empty Stomach In Man

- Table of Contents

- next: III. Tonus And Contractions Of The Empty Stomach In The Newborn Infant