Perigastric Abscess

Description

This section is from the book "Cancer And Other Tumours Of The Stomach", by Samuel Fenwick. Also available from Amazon: Cancer and other tumours of the stomach.

Perigastric Abscess

A localised abscess may occur under three conditions : (1) If idhesions have previously formed around the base of the dissase in such a manner as to prevent extravasation of the gastric contents into the general cavity of the peritoneum; (2) if the initial leakage is so slight as to cause a strictly localised peritonitis, which in its turn helps to circumscribe the products of inflammation; (3) if the perforation occurs in localities which are outside the peritoneum, as, for instance, between the layers of the lesser omentum, in the lesser cavity of the peritoneum, the orifice of which (foramen of Winslow) has been previously obliterated, or in the substance of some solid organ in the neighbourhood.

Frequency

About 10 per cent, of all cases of perigastric abscess arise from malignant disease of the stomach or duodenum ; but its exact frequency in gastric cancer is difficult to determine, since the majority of writers merely refer to the fact of its occurrence without offering any statistical evidence. Brinton found that an intraperitoneal abscess was present in four out of 507 cases (0.8 per cent.), and a similar condition was observed eight times in our own series of 265 autopsies, or in 3 per cent. On the other hand, Osier and McCrae noted its existence in three out of their forty-six cases. It probably occurs in 3 to 5 per cent, of all cases of gastric carcinoma.

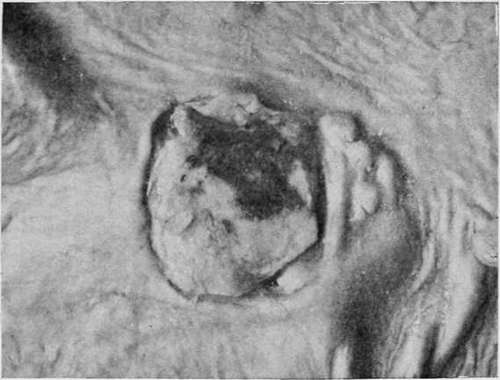

Fig. 25.-A medullary growth which had sloughed and produced perforation of the stomach. (Museum of the Royal College of Surgeons.).

Position And Boundaries

The formation of an abscess is a late phenomenon in gastric cancer. It usually arises in connection with a growth which has destroyed the posterior wall of the viscus near its upper margin, and its sac is then formed by adhesions between the under surface of the liver and the stomach. Less frequently perforation takes place into the lesser cavity of the peritoneum, and the resulting abscess is bounded in front by the stomach, behind by the pancreas, above by the liver, and below by the colon and transverse mesocolon. In such cases the pus may find its way into the duodenum or the colon, or make its way upwards towards the surface of the liver. Next in order of frequency is the formation of an abscess between the lower border of the stomach and the transverse colon, as a result of a growth of the great curvature. In this condition the area of suppuration is strictly limited by adhesions between the two organs, and the sac often discharges its contents into the large bowel. When perforation of the anterior wall of the stomach gives rise to an abscess, the latter is bounded, in front by the abdominal parietes ; behind by the stomach, the small omentum, and perhaps the colon ; above by the liver ; and below by adhesions between the intestines and the wall of the abdomen. In these cases the pus exhibits a tendency to follow the course of the round ligament, and not infrequently points at the umbilicus ; less commonly it tracks along the sides of the gall-bladder towards the upper surface of the right lobe of the liver. In rare instances the sac ruptures and general peritonitis ensues. Subdiaphragmatic suppuration upon the left side is very rare in cancer, and is chiefly encountered in disease of the lesser curvature close to the cardiac orifice. As a rule the abscess is quite small, and its walls are formed by adhesions in the immediate vicinity of the disease ; but when perforation has occurred from the sudden sloughing of the growth, the resulting abscess may closely resemble that which ensues from a simple ulcer in the same situation. In this position its boundaries are remarkably uniform. Above it is limited by the left wing of the diaphragm; below by the upper surface of the left lobe of the liver, and by adhesions between the anterior wall of the stomach and the abdominal parietes; on the right by the falciform ligament ; on the left by the spleen, the gastrosplenic omentum, and by adhesions between the cardiac end of the stomach, spleen, and diaphragm; and in front by the abdominal wall and the diaphragm.

In only about one-quarter of the cases can any direct communication be found between the stomach and the abscess, and in such the perforation often involves a large area of the gastric wall. In the rest the aperture has usually been closed before death by proliferation of the growth or by the formation of adhesions. It is also possible that in some instances the leakage really took place through the spongy substance of the tumour without any actual solution of continuity. When the abscess is small in size, its contents usually consist of thin curdy pus; but in the larger varieties, and in those associated with sloughing of the gastric wall, the inner surface of the sac is often invaded by the neoplasm, and the ichorous fluid it contains is mixed with tags of gangrenous tissue and decomposing food.

Complications

Owing to its comparatively small size, its distance from the diaphragm, and the low vitality of the patient, a perigastric abscess due to cancer is seldom accompanied by any notable symptoms. When it is encysted behind the stomach, the principal indication of its presence is the development of intermittent pyrexia, accompanied by a rapid increase of the general debility; but should the pus come into contact with the diaphragm, it may set up suppurative inflammation of the pleura or pericardium. If the abscess is situated anteriorly, it may discharge itself at the umbilicus or burst into the colon or duodenum ; while in rare instances it ruptures into the cavity of the peritoneum. Perforation of the diaphragm, such as occurs in other varieties, has never been recorded.

Continue to:

- prev: Acute General Peritonitis

- Table of Contents

- next: Perforation Of Neighbouring Organs. A. The Solid Viscera