Mechanical Mobility

Description

This section is from the book "Cancer And Other Tumours Of The Stomach", by Samuel Fenwick. Also available from Amazon: Cancer and other tumours of the stomach.

Mechanical Mobility

Many localised tumours of the stomach may be displaced by pressure with the hand. The most mobile are those situated at the pylorus, which may sometimes be moved several inches in every direction; while occasionally growths of the anterior wall, or of the entire viscus, are susceptible of displacement both vertically and laterally. This form of mobility is diminished or entirely prevented by adhesion of the growth to the liver, pancreas, or abdominal wall, or by its fixation in the upper abdomen by its own bulk.

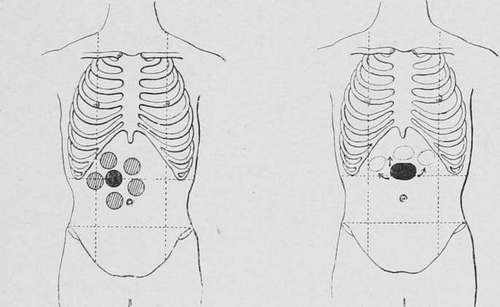

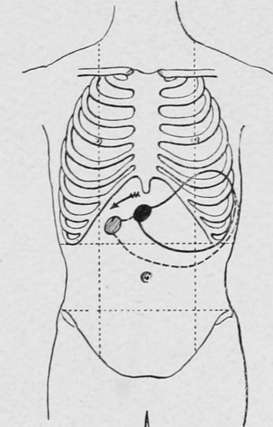

Alterations in the size of the stomach exercise a notable influence upon the position of the tumour. For this reason it is always advisable to record the exact location and apparent size of the growth upon the skin when the viscus is empty, and to repeat the process after the stomach has been distended with water or gas. Under these conditions it may usually be observed : (1) That tumours of the upper margin which were not palpable in the first instance become apparent when the stomach is inflated; (2) that tumours of the pylorus descend downwards and to the right, those of the great curvature downwards, and those of the fundus downwards and to the left ; (3) that growths of the anterior surface become more distinct, and often ascend slightly, owing to the upward rotation of the wall of the organ. Conversely, a patient who exhibits great dilatation of the stomach with an ill-defined tumour in the right hypochondrium when first examined, will often present a comparatively large tumour in the epigastrium, or even in the left hypochondrium, when the organ has been emptied by a tube, owing to the diminution in the bulk of the stomach pulsation. This phenomenon was never observed with growths of the cardia, and was five times as frequent in tumours of the pylorus as in those of the body of the stomach. The movement is invariably derived from the underlying aorta, and is therefore antero-posterior in direction and never eccentric, as in cases of aneurysm. Occasionally the aorta itself is displaced to the right by the mass, or it is so compressed that it becomes dilated above the site of its obstruction (Ott). According to Gabbi, compression of the aorta or of the cceliac axis by a diffuse growth may produce a thrill and a loud systolic bruit. In one of our cases an abdominal aneurysm and the consequent retreat ot the pylorus towards the median line.

Fig. 41.-Showing the mobility of a Fig. 42.-Showing the mobility of a pyloric tumour when free from adgrowth of the anterior wall when hesions. free from adhesions.

The condition of the transverse colon also produces a notable effect upon the location and palpability of a gastric tumour. Thus, many growths appear to descend and to become more distinct after the bowels have been evacuated, while distension of the colon with gas causes them to ascend, and sometimes to become obscured beneath the margin of the ribs.

(I) Pulsation

In 17 per cent, of our cases the tumour was stated to have exhibited coexisted with carcinoma of the pylorus, and led to an erroneous diagnosis.

Fig. 43.- Showing the movement of a pyloric tumour upon inflation of the stomach.

(J) Percussion

When the tumour is situated immediately behind the abdominal wall, light percussion produces a dull note and strong percussion a form of tympanitic dulness. A large intragastric growth attached to the upper margin or the posterior surface is usually comparatively dull when the stomach is empty, but presents a tympanitic note when the viscus is filled with gas. The percussion-note over tumours of the pylorus and of the great curvature is often obscured by a superimposed and adherent colon.

(K) Auscultation

Gurgling sounds may often be detected over the pylorus during the efforts of the hypertrophied stomach to force its contents through the contracted orifice, and a similar phenomenon may sometimes be heard at the centre of the viscus in cases of hour-glass stricture. Stenosis of the cardia is associated with retardation or entire suppression of the deglutition sounds. Occasionally pressure of the growth upon the aorta or cceliac axis produces a systolic murmur, which is audible over the epigastrium and back.

(I) Increase Of Size

All varieties of carcinomatous tumours exhibit an increase of size, which is most rapid in the softer forms of growth.

Changes of shape or the development of a nodular surface usually indicate an extension of the disease to the peritoneum or other neighbouring structures.

Diminution or disappearance of the tumour is occasionally observed when the major portion of the growth has been destroyed by sloughing, or after the establishment of an internal fistula.

Continue to: