Chapter VII. Kitchen Gardening Under Elizabeth And James I

Description

This section is from the book "A History Of Gardening In England", by Alicia Amherst. Also available from Amazon: A History Of Gardening In England.

Chapter VII. Kitchen Gardening Under Elizabeth And James I

" Whose golden gardens seeme th' Hesperides to mock.

Nor these the Damson wants nor daintie Abricock.

Nor Pippin, which we hold of kernel fruits the king.

The Apple-Orendge, then the sauory Russetting.

The Peare-maine which to France long ere to us was knowne.

Which carefull Frut'rers now haue denizend our owne * * * * *.

The sweeting, for whose sake the Plowboyes oft make warre The Wilding, Costard, then the wel-known Pomwater And Sundry other fruits of good yet severall taste That haue their sundry names in sundry counties plac't".

Drayton, Polyolbion.

THE changes in the kitchen, or "cooks-garden,"* were not so marked as in the " garden of pleasant flowers." † As the flower-garden lay in front of the house, " in sight and full prospect of all the chief and choicest roomes of the house ; so contrariwise, your herbe garden should be on the one or other side of the house . . . for the many different sents that arise from the herbes, as cabbages, onions, etc, are scarce well pleasing to perfume the lodgings of any house." This is certainly a change from the gardens of earlier times, when herbs covered more or less the whole area of the average garden, when groundsel was allowed a place with leeks, thyme, and lettuce, and was classed among garden herbs indiscriminately with periwinkles, roses, and violets.

Holinshed (died 1580), describing England in his day, points out that the cultivation of vegetables was greatly increased, and says that vegetables "have been very plentiful in this land in the time of the first Edward, and after his daies, but in process of time they grew also to be neglected, so that from Henry the Fourth till the latter end of Henry the Seventh and beginning of Henry the Eighth, there was little or no use of them in England, but they remained either unknown or supposed as food more meet for hogs and savage beasts to feed upon than mankind. Whereas in my time their use is not onelie resumed among the poore commons, I meane of melons, pompions, gourds, cucumbers, radishes, skirets, parsnips, carrets, cabbages, nauewes, turnips, and all kinds of salad herbes, but also feed upon as deintie dishes at the tables of delicate merchants, gentlemen and the nobilitie, who make their prouision yearelie for new seeds out of strange countries." Hohnshed was writing to extol Elizabeth's reign, and though a faithful chronicler of contemporary events, would be tempted to colour them in order to enhance the glory of the period he was describing. Although vegetables were now more fashionable and more used, still from what we have seen of the gardens of earlier times, it seems incredible that the neglect of them had been so entire as Holinshed would have us believe. Parkinson advises some vegetable seeds to be obtained from abroad, especially melons, but says of many of those on Holin-shed's list of seeds to be obtained from "strange countries, Redish, Lettice, Carrots, Parsneps, Turneps, Cabbages, and Leekes . . . our English seede ... is better than any that cometh from beyond the seas".

* Letter from Peter Kemp to Cecil, 1561. † Parkinson.

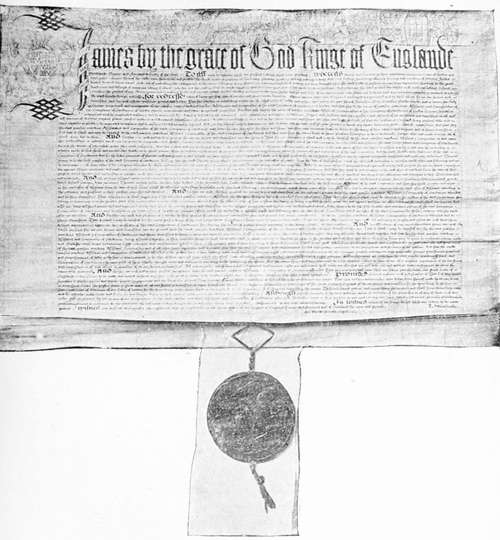

A striking proof of the progress gardening was making during this period, was the growing importance of those practising the craft in and around London, until at length, in the third year of King James I., they attained the dignified position of a Company of the City of London, incorporated by Royal charter. In that year all those "persons inhabiting within the Cittie of London and sixe miles compas therof doe take upon them to use and practice the trade, crafte or misterie of gardening, planting, grafting, setting, sowing, cutting, arboring, kocking, mounting, covering, fencing and removing of plantes, herbes, seedes, fruit trees, stock sett, and of contryving the conveyances to the same belonging, were incorporated by the name of Master Wardens, Assistants and Comynaltie of the Companie of Gardiners of London."* Thomas Young was appointed first Master, and seven years was the term of apprenticeship to the Company.

Charter of the gardener's company.

* From the Original Charter belonging to the Company.

It was hoped that the formation of this Guild would put a stop to frauds practised by gardeners in the City, who sold dead trees and bad seeds " to the great deceit and loss " of their customers. But it appears that these abuses continued to exist, and a second Charter was granted in the fourteenth year of James I.-, and the Company was invested with further privileges. No person was allowed to " use or exercise the art or misterie of gardening, within the said area, without the licence and consent" * of the Company, nor were any persons who had not served their apprenticeship, and received the freedom of the Company permitted to sell any garden-stuff, except within certain hours, and in such places and markets as were open to other foreigners who had not the freedom of the City. The Company were also permitted to seize any " plants, herbs or roots that were exposed for sale by any unlicenced person and distribute them among the poor of the place where such forfeitures shall be taken." And it was also lawful for any four members of the Guild "to search and viewe all manner of plants, stocks, setts, trees, seedes, slippes, roots, flowers, hearbes and other things that shall be sould or sett to sale in any markett within the Cittie of London and sixe myles about," and to " burn or otherwise consume " all that was found to be " unwholesome, dry, rotten, deceitfull or unprofitable." William Wood was elected first Master under the new charter. There were two Wardens, the number of Assistants was increased to twenty-four, a Beadle was appointed, and the Company was granted a livery. The rights and privileges of the Company were again confirmed by Charles I., in 1635. The arms are a man digging, and the supporters two female figures with cornucopiae; the crest, a basket of fruit, and the Motto, " In the sweat of thy browes shalt thou eate thy bread." Although licenced by the Charter, to have a Hall in which to assemble, they never appear to have possessed one. The Company for long has ceased to exercise its privileges, but it still exists, and ranks seventieth among the City Guilds. †

Continue to:

- prev: The Maske Of Flowers

- Table of Contents

- next: Kitchen Gardening Under Elizabeth And James I. Part 2