Appendix

Description

This section is from the book "A Manual Of Photography", by Robert Hunt. Also available from Amazon: A Manual of Photography.

Appendix

The following correspondence, important in the history of photography, appeared in the Times newspaper of August 13,1852 :— the photographic patent right.

We have been requested to publish the following correspondence between the Presidents of the Royal Society and the Royal Academy, and the patentee of the art of photography upon paper, with the view of definitively settling a question of considerable interest to artists and amateurs of photography in general :—

No. 1

London, July. 1852.

Dear Sir,—In addressing to you this letter, we believe that we speak the sentiments of many persons eminent for their love of science and art.

The art of photography upon paper, of which you are the inventor, has arrived at such a degree of perfection that it must soon become of national importance ; and we are anxious that, as the art itself originated in England, it should also receive its further perfection and development in this country. At present, however, although England continues to take the lead in some branches of the art, yet in others the French are unquestionably making more rapid progress than we are.

It is very desirable that we should not be left behind by the nations of the Continent in the improvement and development of a purely British invention; and as you are the possessor of a patent right in this invention, which will continue for some years, and which may, perhaps, be renewed, we beg to call your attention to the subject, and to inquire whether it may not be possible for you, by making some alteration in the exercise of your patent rights, to obviate most of the difficulties which now appear to hinder the progress of the art in England. Many of the finest applications of the invention will, probably, require the co-operation of men of science and skilful artists. But it is evident that the more freely they can use the resources of the art, the more probable it is that their efforts will be attended with eminent success.

As we feel no doubt that some such judicious alteration would give great satisfaction, and be the means of rapidly improving this beautiful art, we beg to make this friendly communication to you, in the full confidence that you will receive it in the same spirit—the improvement of art and science being our common object.

ROSSE.

C. L. EASTLAKE.

To H. F. Talbot, Esq., F.R.S., etc.

Lacock Abbey, Wilts.

No. 2

Lacock Abbey, July 30.

My Dear Lord Rosse,—I have had the honour of receiving a letter from yourself and Sir C. Eastlake respecting my photographic invention, to which I have now the pleasure of replying.

Ever since the Great Exhibition, I have felt that a new era has commenced for photography, as it has for so many other useful arts and inventions. Thousands of persons have now become acquainted with the art, and, from having seen such beautiful specimens of it produced both in England and France, have naturally felt a wish to practise it themselves. A variety of new applications of it have been imagined, and doubtless many more remain to be discovered.

I am unable myself to pursue all these numerous branches of the invention in a manner that can even attempt to do justice to them, and moreover, I believe it to be no longer necessary, for the art has now taken a firm root both in England and France, and may safely be left to take its natural development. I am as desirous as any one of the lovers of science and art, whose wishes you have kindly undertaken to represent, that our country should continue to take the lead in-this newly-discovered branch of the fine arts; and, after much consideration, I think that the best thing I can do, and the most likely to stimulate to further improvements in photography, will be to invite the emulation and competition of our artists and amateurs, by relaxing the patent right which I possess in this invention. I therefore beg to reply to your kind letter by offering the patent (with the exception of the single point hereafter mentioned), as a free present to the public, together with my other patents for improvements in the same art, one of which has been very recently granted to me, and has still thirteen years unexpired. The exception to which I refer, and which I am desirous of still keeping in the hands of my own licensees, is the application of the invention to taking photographic portraits for sale to the public. This is a branch of the art which must necessarily be in comparatively few hands, because it requires a house to be built or altered on purpose, having an apartment lighted by a skylight, etc., otherwise the portraits cannot be taken indoors, generally speaking, without great difficulty.

With this exception, then, I present my invention to the country, and trust that it may realize our hopes of its future utility.

Believe me to remain, my dear Lord Rosse,

Your obliged and faithful servant,

H. F. TALBOT

The Earl of Rosse, Connaught Place, London.

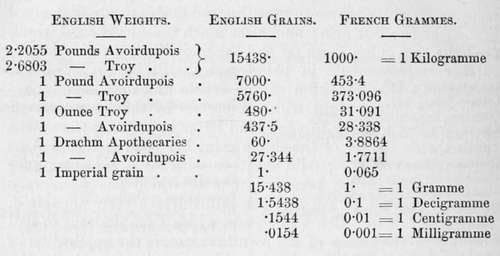

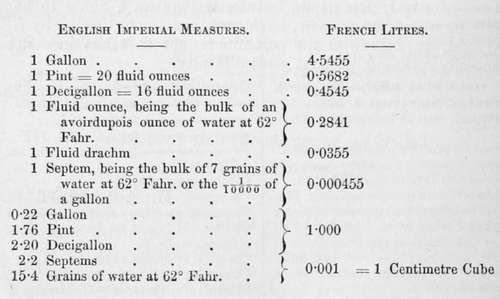

Correspondence Of English And French Weights And Measures

Continue to:

- prev: Photographic Engraving. Continued

- Table of Contents

- next: Cabinet Edition Of The Encyclopaedia Metropolitan