Appendix. Part 11

Description

This section is from the book "Breeding, Training, Management, Diseases Of Dogs", by Francis Butler. Also available from Amazon: Breeding, training, management, diseases.

Appendix. Part 11

When Mr. M. has company, if he desires the dog to see any one of the gentlemen home, it will walk with him till he reach his home, and then return to his master, how great soever the distance may be. A brother of Mr. M.'s and another gentleman went one day to Newhaven, and took Dandie along with them. After having bathed, they entered a garden in the town ; and having taken some refreshment in one of the arbors, they took a walk around the garden, the gentleman leaving his hat and gloves in the place. In the meantime some strangers came into the garden, and went into the arbor which the others had left. Dandie immediately, without being ordered, ran to the place and brought off the hat and gloves, which he presented to the owner. One of the gloves, however, had been left; but it was no sooner mentioned to the dog than he rushed to,the place, jumped again into the midst of the company, and brought off the glove in triumph.

A gentleman living with Mr. M'Intyre, going out to supper one evening, locked the garden-gate behind him, and laid the key on the top of the wall, winch is about seven feet high. When he returned, expecting to let himself in the same way, to his great surprise the key could not be found, and he was obliged to go round to the front door, which was a considerable distance about. The next morning strict search was made for the key, but still no trace of it could be discovered. At last, perceiving that the dog followed him wherever he went, he said to him, " Dandie, you have the key—go, fetch it" Dandie immediately went into the garden and scratched away the earth from the root of a cabbage, and produced the key, which •he himself had undoubtedly hid in that place. If his master places him on a chair, and requests him to sing, he will instantly commence howling, high, or low, as signs are made to him with the finger.

About three years ago a mangle was sent by a cart from the warehouse, Regent Bridge, to Portobello, at which time the dog was not present. Afterwards, Mr. M. went to his own house, North Back of the Canongate, and took Dandie with him, to have the mangle delivered. When he had proceeded a little way the dog ran off, and he lost sight of him. He still walked forward ; and in a little time he found the cart in which the mangle was, turned towards Edinburgh, with Dandie holding fast by the reins? and the carter in the greatest perplexity; the man stated that the dog had overtaken him, jumped on his cart, and examined the mangle, and then had seized the reins of the horse and turned him fairly round, and that he would not let go his hold, although he had beaten him with a stick. On Mr. M.'s arrival however, the dog quietly allowed the carter to proceed to his place of destination.

" Tag," a large Newfoundland dog was put to work in a dog power wheel used for churning purposes, but from the first showed a decided dislike for labor. Having been hurt in a fore foot a few months afterwards, he had a rest for a couple of weeks to permit of his foot getting well. When put in the power again he refused to turn it, but held up the foot that had been lame, and howled as if in great pain. His owner supposing that he had perhaps strained the lame foot, let him out, and Tag limped off on three legs, but was soon discovered dashing across a meadow in company with a neighbor's dog, as though he had never been lame. He was called in and again put in the power, and again held up his foot and howled, but a cut or two of the whip convinced him that his trick was seen through, so he went dogfully to work, and nothing of Tag's lameness was afterward seen.

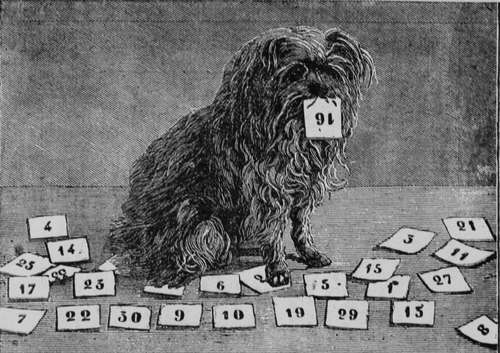

Minos, The Learned Dog

A very learned man has just written a long article for one of the magazines to prove that dogs, horses and birds have souls. Of course we cannot ail agree with him ; but we are ready enough to admit that these creatures have minds, —pretty active ones too—whether they have souls or not. Minos, the dog, on page 184, is a wonderful little fellow. He came from Havana, and is now being exhibited in France. His mistress, Madame Hager, has taught him to answer questions which would puzzle some children seven years old. He finds a given number correctly ; works out examples in addition, subtraction and division; he can read words that are written and placed before him, and indeed does so many remarkable things that fashionable people in Paris are glad to have him and his mistress visit them at their elegant houses.

Now if a poor dumb dog can learn so much by being simply attentive and obedient, what ought we not to expect of wide-awake boys and girls who can talk, and have not only active minds, but souls as well?

Air. Youatt gives the following anecdote as a proof of the reasoning power of a Newfoundland dog.

Waiting one day to go through a tall iron gate, from one part of his premises to another, he found a lame puppy lying just within it, so that he could not get in without rolling the poor animal over, and perhaps injuring it. Mr. Youatt stood for awhile hesitating what to do, and at length determined to go round through another gate. A fine Newfoundland dog, however, who had been waiting patiently for his wonted caresses, and perhaps wondering why his master did not get in as usual, looked accidentally down at his lame companion. He comprehended the whole business in a moment— put down his great paw, and as gently and quickly as possible rolled the invalid out of the way, and then drew himself back in order to leave room for the opening of the gate.

We may be inclined to deny reasoning faculties to dogs : but if this was not reason, it may be difficult to define what else it could be.

Mr. Youatt also says, that his own experience furnishes him with an instance of the memory and gratitude of a Newfoundland dog, who was greatly attached to him. He says, as it became inconvenient to him to keep the dog, he gave him to one who he knew would treat him kindly. Four years passed, and he had not seen him; when one day as he was walking towards Kingston, he met Carlo and his master. The dog recollected Mr. Youatt in a moment, and they made much of each other. His master, after a little chat, proceeded towards Wandsworth, and Carlo, as in duty bound, followed him. Mr. Youatt had not, however, got halfway down the hill when the dog was again at his side, lowly but deeply growling, and every hair bristling. On looking about, he saw two ill-looking fellows making their way through the bushes, which occupied the angular space between Rockhampton and Wandsworth roads. Their intention was scarcely questionable, and, indeed, a week or two before, he had narrowly escaped from two miscreants like them. " I can scarcely say," proceeds Mr. Youatt, " what I felt; for presently one of the scoundrels emerged from the bushes, not twenty yards from me; but he no sooner saw my companion, and heard his growling, the loudness and depth of which were fearfully increasing, than he retreated, and I saw no more of him or his associate. My gallant defender accompanied me to the directicm-post at the bottom of the bill, and there, with many a mutual and honest greeting, we parted, and he bounded away to overtake his rightful owner. We never met again ; but I need not say that I often thought of him with admiration and gratitude."

Continue to: