Starting And Alighting. Part 2

Description

This section is from the book "The New Art Of Flying", by Waldemar Kaempffert. Also available from Amazon: The New Art of Flying.

Starting And Alighting. Part 2

" On the 24th another trip was made and another day spent ineffectively on account of the wind. On the 27th there was a similar experience, and here four days and four (round-trip) journeys of sixty miles each had been spent without a single result. This may seem to be a trial of patience, but it was repeated in December, when five fruitless trips were made, and thus nine such trips were made in these two months and but once was the aerodrome even attempted to be launched, and this attempt was attended with disaster. The principal cause lay, as I have said, in the unrecognised amount of difficulty introduced even by the very smallest wind, as a breeze of three or four miles an hour, hardly perceptible to the face, was enough to keep the airship from resting in place for the critical seconds preceding the launching.

" If we remember that this is all irrespective of the fitness of the launching piece itself, which at first did not get even a chance for trial, some of the difficulties may be better understood; and there were many others.

" During most of the year of 1894 there was the same record of defeat. Five more trial trips were made in the spring and summer, during which various forms of launching apparatus were tried with varied forms of disaster. Then it was sought to hold the aerodrome out over the water and let it drop from the greatest attainable height, with the hope that it might acquire the requisite speed of advance before the water was reached. It will hardly be anticipated that it was found impracticable at first to simply let it drop without something going wrong, but so it was, and it soon became evident that even were this not the case, a far greater time of fall was requisite for this method than that at command. The result was that in all these eleven months the aerodrome had not been launched, owing to difficulties which seem so slight that one who has not experienced them may wonder at the trouble they caused.

Fig. 15. Blériot starting from the French coast on his historic flight across the English Channel.

Photograph by Edwin Levick.

" Finally, in October, 1894, an entirely new launching apparatus was completed, which embodied the dozen or more requisites, the need for which had been independently proved in this long process of trial and error. Among these was the primary one that it was capable of sending the aerodrome off at the requisite initial speed, in the face of a wind from whichever quarter it blew, and it had many more facilities which practice had proved indispensable".

Langley's account has a certain historical interest, because never before had a motor-driven machine been brought to such a pitch of perfection that it could fly, if once launched. After his repeated failures, Langley finally succeeded in launching his craft from " ways," as shown in Fig. 11, somewhat as a ship is launched into the water, the machine resting on a car, which fell down at the end of the car's motion.

A launching device identical in principle was afterwards employed to start the man-carrying machine built by Langley for the United States Government. Once, according to Major Macomb, of the Board of Ordnance, " the trial was unsuccessful because the front guy post caught in its support on the launching car and was not released in time to give free flight, as was intended, but, on the contrary, caused the front of the machine to be dragged downward, bending the guy post and making the machine plunge into the water about fifty yards in front of the house boat." Of another trial Major Macomb states ..." the car was set in motion and the propellers revolved rapidly, the engine working perfectly, but there was something wrong with the launching. The rear guy post seemed to drag, bringing the rudder down on the launching ways, and a crashing, rending sound, followed by the collapse of the rear wings, showed that the machine had been wrecked in the launching; just how it was impossible to see".

Because it was never launched, the machine never flew. The appropriation having been exhausted, Langley was compelled to abandon his tests. The newspaper derision which greeted him undoubtedly embittered him, shortened his life, and probably set back the date of the man-carrying flying-machine's advent several years. Langley's trials have been here set down at some length to show the practicability and impracticability of various launching methods and to demonstrate that his machine was far from being the failure popularly supposed. No man has contributed so much to the science of aviation as the late Samuel Pier-pont Langley.

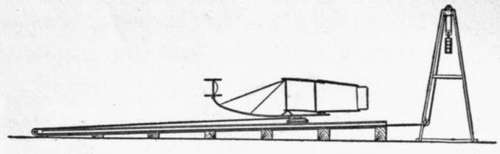

That his work was not lost on the Wright Brothers at least, is evidenced by the manner in which they attacked the difficulty of getting up starting speed. The Wright Brothers invented an arrangement, which was simpler than Langley's, more efficient, and not so likely to imperil the aeroplane. As illustrated in Figures 12 and 13, it consisted in its early stage of an inclined rail, about seventy feet long; a pyramidal " derrick"; a heavy weight arranged to drop within the derrick; and a rope which was fastened to the weight, led around a pulley at the top of the derrick, passed around a second pulley at the bottom of the derrick and over a third pulley at the end of the rail, and then secured to a car. The car was placed on the rail, and the aeroplane itself on the car. When a trigger was pulled, the weight fell, and the car was jerked forward. So great was the preliminary velocity thus imparted that the machine was able to rise from the car in a few seconds.

Continue to: