Flying Machines Of To-Day. Part 7

Description

This section is from the book "All About Flying", by Gertrude Bacon. Also available from Amazon: All About Flying.

Flying Machines Of To-Day. Part 7

In all the half-hour that we were up, circling, turning and banking, my pilot—Gordon England— did not once have occasion to touch the ailerons. Ailerons indeed seem growing obsolete, if only because at the high speeds now reached there simply is not time for them to take effect. We travelled, for the most part, at 80 miles an hour; but with the propeller behind and a wind-screen in front the draught was not even inconvenient. Very different had been my experience flying at 70 miles an hour in a ' Dep ' hydro-monoplane at Windermere, where the 'slip-stream' of the tractor, just behind which I sat, had seemed to blow the breath from my nostrils and the eyes out of my head.

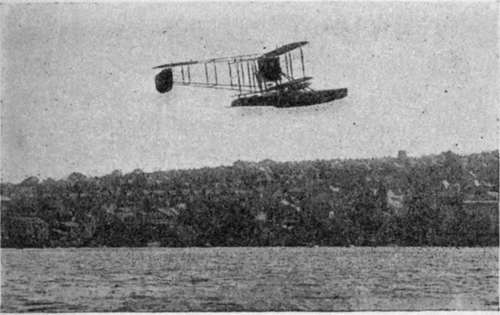

Great luck was mine at Cowes that day, for presently there swept overhead, from the naval station at Calshot, a Sopwith 'bat-boat' flying strong and steady. The Sopwith Company supply yet another splendid example of an English firm which can compete with the whole world. In proof of this a Sopwith single-seater tractor hydro-biplane, 100 horsepower Gnome engine, flying at over 90 miles an hour, piloted by Howard Pixton, carried off the Schneider Cup at Monaco in April 1914—the first British machine to win a big international race. The Sopwith ' bat-boat' (the word is derived from Kipling's immortal story With the Night Mail) is a most successful example of a water-plane where the place of the floats is taken by an actual boat in which the aviator sits. Curtiss has evolved several flying boats of this description, one of which, it is hoped, will make the Atlantic crossing. Practically all the great continental aeroplane firms have turned their attention recently to hydro-aeroplanes. Let us hope that England may long hold the lead she has undoubtedly won.

Sopwith Sea-Planes

The Bat-Boat.

100 H.R. Tractor Sea-Plane.

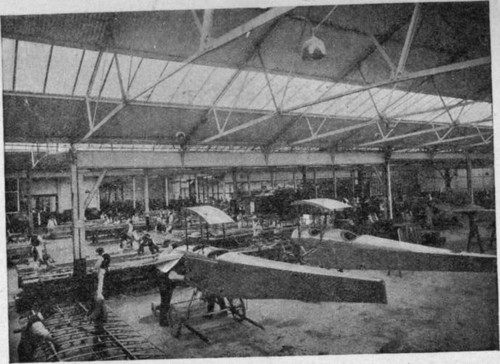

And now just a few last words, in an overlong chapter, concerning the actual manufacture of the aerial craft we have been discussing. Even before the War this was going on in many places : at Short's • factory in the Isle of Sheppey, with a newly opened sea-plane branch in the Medway; at the busy Sopwith works at Kingston-on-Thames, the Avro works in Manchester, Vicars at Erith, Grahame-White's and others at Hendon ; at Brooklands, where is a large factory of British-made Bleriots, as well as the Martinsyde and other shops ; at Farnborough, Cowes, and elsewhere.

Chief among those of 'the trade ' who have reaped the benefit of foresight and enterprise, must certainly be counted Sir George White, of Bristol electric-car fame. Right back at the very commencement of aviation, when the idea that flight had any commercial possibilities about it was openly scouted, he read aright the signs of the times, and founded, in May 1910, the British and Colonial Aeroplane Company works at Filton, on the outskirts of Bristol, which in peace time employs three or four hundred men, and is capable of turning out an aeroplane a day. Here are built aeroplanes for the governments of many foreign nations, and large numbers of 'B.E. 2's' and other craft for the War Office and Admiralty. (The wicker-work pilots' seats for the military machines, by the way, are specially manufactured by the blind at the Bristol Blind School.) Within the huge sheds we may watch the whole process of the building of an aeroplane, from the stacks of rough planks to the completed machine. The question of wood is becoming a very serious one. Ash is the favourite for spars and framework, as being light and tough and springy. But it must be English ash, slowly grown, long and straight, and not too old. Ash trees take long in growing, the demand is great and ever increasing; the supply grows rapidly less and prices rise in proportion. Already spruce from Russia is being used in larger and larger quantities wherever possible, and the dearth of suitable wood will hasten the arrival of all-steel machines.

Building Aeroplanes At The Bristol Works.

Carpenters' shops, metal-workers' shops, and all the costly and elaborate machinery they entail, forges, drawing offices, laboratories, have their part in the busy factory; not to mention the rooms where the closely woven cotton fabric, costing 2s. 2d. a yard and more, is stretched upon the wings, and then plentifully 'doped' with special preparation, which makes it weatherproof, smooth and taut. There is apparatus for the careful testing of the propellers, rooms where the engines are put through their paces. Finally the whole machine is 'assembled' preparatory to being packed up and dispatched to the flying-ground, where first it spreads its spotless wings for flight.

Continue to: