Chapter X. Medieval Hospitals

Description

This section is from the book "Medieval Medicine", by James J. Walsh. Also available from Amazon: Medieval Medicine..

Chapter X. Medieval Hospitals

Our recent experience makes it easy to understand that such magnificent advance in surgery as has been described in the preceding chapters would have been quite impossible unless there were excellent hospitals in the medieval period. Good surgery demands good hospitals, and indeed inevitably creates them. Whenever hospitals are in a state of neglect, surgery is hopeless. We have, however, abundant evidence of the existence of fine hospitals in the Middle Ages, quite apart from this assumption of them, because of the surprising surgery of the period. Historical traditions from the earlier as well as the later medieval times demonstrate a magnificent development of hospital organization. While there had been military hospitals and a few civic institutions for the care of citizens in Roman times, and some hospital traditions in the East and in connection with the temples in Egypt, hospital organization as we know it is Christian in origin ; and particularly the erection of institutions for the care of the ailing poor came to be looked upon very early as a special duty of Christians. Even the Roman Emperor, Julian the Apostate, declared that the old Olympian religion would inevitably lose its hold on the people, unless somehow it could show such care for others in need as the Christians exhibited wherever they obtained a foothold. It was not, however, until nearly the beginning of the Middle Ages that the Christians were in sufficient numbers in the cities, and were free enough from interference by government, to take up seriously the problem of public hospital organization. The rapidity of the development, once external obstacles were removed, shows clearly how close to the heart of Christianity was the subject of care for the ailing poor. St. Basil's magnificent foundation at Caesarea in Cappadocia, called the Basilias, which took on the dimensions of a city (termed Newtown) with regular streets, buildings for different classes of patients, dwellings for physicians and nurses and for the convalescent, and apparently even workshops and industrial schools for the care and instruction of foundlings and of children that had been under the care of the monastery, as well as for what we would now call reconstruction work, shows how far hospital organization, even in the latter part of the fourth century, had developed.

About the year 400 Fabiola at Rome, according to St. Jerome, " established a Nosocomium to gather in the sick from the streets, and to nurse the wretched sufferers wasted from poverty and disease." A little later Pammachius, a Roman Senator, founded a Xenodochium for the care of strangers which St. Jerome praises in one of his letters. At the end of the fifth century Pope Symmachus built hospitals in connection with the three most important churches of Rome, St. Peter's, St. Paul's, and St. Lawrence's. During the Pontificate of Vigilius, Belisarius founded a Xenodochium in the Via Lata at Rome, shortly after the middle of the sixth century. Christian hospitals were early established in the cities of France; and not long after the conversion of England, in that country.

In connection with these hospitals, it is rather easy to understand the fine development of surgery by early Christian physicians which we have traced. The later medieval period of hospital building, however, is of particular interest in the history of medicine, because we have such details of it as show its excellent adaptation to medical and surgical needs. According to Virchow, in his article on the History of German Hospitals, which is to be found in the second volume of his collected " Essays on Public Medicine and the History of Epidemics,"* the story of the foundation of these hospitals of the Middle Ages, even those of Germany, centres around the name of one man, Pope Innocent III. Virchow was not at all a papistically inclined writer, so that his tribute to the great Pope who solved so finely the medico-social problems of his time undoubtedly represents a merited recognition of a great social development in history.

" The beginning of the history of all these German hospitals is connected with the name of that Pope who made the boldest and farthest-reaching attempt to gather the sum of human interests into the organization of the Catholic Church. The hospitals of the Holy Ghost were one of the many means by which Innocent III. thought to hold humanity to the Holy See. And surely it was one of the most effective. Was it not calculated to create the most profound impression to see how the mighty Pope, who humbled emperors and deposed kings, who was the unrelenting adversary of the Albigenses, turned his ej^es sympathetically upon the poor and the sick, sought the helpless and the neglected upon the streets, and saved the illegitimate children from death in the waters ! There is something at once conciliating and fascinating in the fact that, at the very time when the fourth crusade was inaugurated through his influence, the thought of founding a great organization of an essentially humane character, which was eventually to extend throughout all Christendom, was also taking form in his soul; and that in the same year (1204) in which the new Latin Empire was founded in Constantinople, the newly erected hospital of the Holy Spirit, by the old bridge on the other side of the Tiber, was blessed and dedicated as the future centre of this organization".

* " Gesammelte Abhandlungen aus dem Gebiete der Oeffentliche Medizin," Hirschwald, Berlin, 1877.

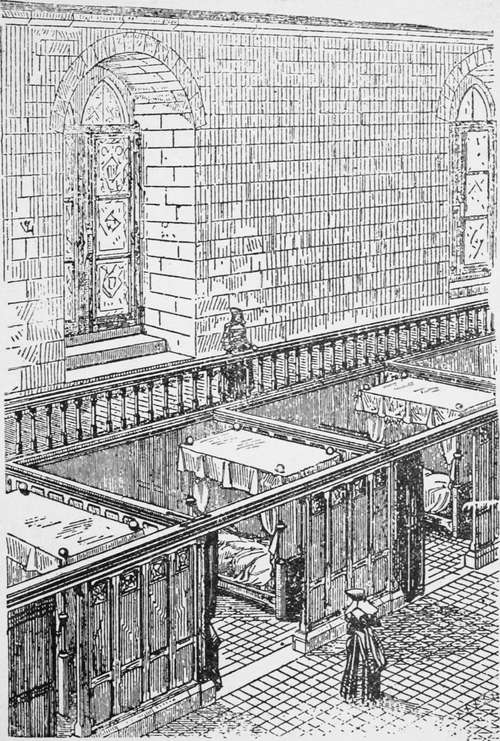

Thirteenth-Century Hospital Interior (Tonerre) From 11 The Thirteenth: Greatest Of Centuries;* By J. /. Walsh.

According to tradition, just about the beginning of the thirteenth century Pope Innocent resolved to build a hospital in Rome. On inquiry, he found that probably the best man to put in charge of hospital organization was Guy or Guido of Mont-pellier, of the Brothers of the Holy Ghost, who had founded a hospital at Montpellier which became famous throughout Europe for its thorough organization. Accordingly he summoned Guido to Rome, and gave into his hands the organization of the new hospital, which was erected on the other side of Tiber in the Borgo not far from St. Peter's. Indeed, Santo Spirito Hospital, as it came to be called, was probably the direct successor of the hospital which Pope Symmachus (488-514) had had built in connection with St. Peter's not long after the beginning of the Middle Ages. It is easy to understand that at the time when magnificent municipal structures, cathedrals, town halls, abbeys, and educational institutions of various kinds were being erected, with exemplary devotion to art and use, the Hospital of Santo Spirito under the special patronage of the Pope was not unworthy of its time.* We know very little, however, about the actual structure.

Continue to: