Chapter IX. Road Side Scenes

Description

This section is from the book "Ceylon", by Alfred Clark. Also available from Amazon: Ceylon.

Chapter IX. Road Side Scenes

As their dark, windowless little huts are only suitable to sleep in, or to take shelter in when it rains, the greater part of the time of natives is spent in the open air. Consequently, many curious sights are to be seen in the streets.

The whole process of preparing the midday meal, the boiling of the rice, the slicing of the vegetables, the scraping of the coconut and the grinding of the curry stuff may be seen from beginning to end. The food is often partaken of, first by the silently, or frequent the mango-groves, where they do great destruction to the fruit, fighting and squealing the while. So noisy and quarrelsome are they sometimes that the natives account for it by saying that they are all intoxicated through drinking the fermented toddy in the pots hanging in the coconut-trees ! Sometimes the hideous cry of the devil-bird, a species of owl, may be heard. The trees are ablaze with the flickering light of myriads of fire-flies, and the whir of the cicada beetle and the hum of clouds of mosquitoes over stagnant pools may be distinctly heard.

When not engaged in domestic duties, the women sit before their houses weaving mats, twisting coir yarn, or making lace, an art they have practised in the Galle district since Portuguese times.

Glimpses may sometimes be got of a devil ceremony going on at the back of some house, for the benefit of some sick person. A kapurdla, or exorciser, clad in a fantastic costume, stands on a low stool, and shaking an iron trident with loose rings on it over the patient, pours out a string of charms, the meaning of which he does not understand. They are fragments of ancient exorcisms in a dead language, handed down verbally from generation to generation.

Children and pariah dogs swarm everywhere. Most of the latter are practically masterless, and live on what they can pick up. They became so numerous that Government determined to reduce their numbers, and offered rewards for their destruction. In the first year in which this was done in one of the larger towns eleven hundred dogs were shot in a few days!

In little booths open to the street native craftsmen may be seen at work, such as carpenters making furniture of yellow jak-wood, or repairing hackeries. Two of them may often be seen working one plane, one pushing and the other pulling the tool, this being necessary owing to the extreme hardness of some of the woods worked. Ebony-carvers, tortoiseshell-workers, and makers of porcupine-quill boxes squat at their work open to the view of all. Sometimes a silversmith is to be seen sitting at his little bench before the door of a house, fashioning bangles and other ornaments with the same kind of tools as were employed two thousand years ago. The natives have a proverb which says, " There is no monkey but is mischievous, no woman but is a tattler, and no silversmith but is a thief !" A sharp lookout is accordingly kept, lest the silversmith should substitute base metal for the rupees given to him to be made into jewellery.

At the galas, or cart halting-places, the strange process of shoeing bullocks may often be witnessed. The animals are thrown down, their four legs are tied together, and light iron shoes nailed on to their cloven hoofs. Without this protection their hoofs would soon be worn to the quick by the hard work of dragging heavy carts. The feeding of cart-bullocks with punac, or coconut refuse, is another strange sight. The cake is broken up and dissolved in a small tub, into which the carter dips a sort of bamboo bottle, and, forcing open the bullock's mouth and holding its head high, pours the evil-smelling stuff down its throat.

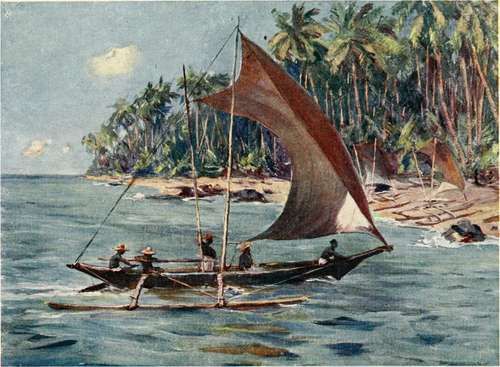

Singhalese Sailing Canoe.

The streets are full of men and women, whose appearance and doings are full of interest to those not familiar with Eastern life. Men pass continually, carrying pingoes, or elastic shoulder-poles, at the ends of which hang loads of fish, fruit, or other commodities. The bending of the pingo at each step and swing of the laden man greatly facilitates the carrying of heavy burdens. Combed and petticoated appus, or Singhalese servants, and Tamil " boys " in white clothes and turbans, go in and out of the boutiques buying provisions for their masters' households.

In front of a boutique may often be seen a yellow-robed Buddhist priest, bowl in hand, waiting for a dole for his monastery from the shopkeeper. He stands with eyes cast down and an impassive look on his face. His shaven head makes his ears look unnaturally large. If the boutique-keeper puts a handful of rice, or a few plantains, or other gift into his bowl, he moves away in silence, and without any acknowledgment of the donor's gift or reverence.

Wandering monkey-tamers and snake-charmers often give their performances in the street. The fangs of the cobras handled by the latter are always drawn, and they are harmless. The snake-charmers, however, frequently pretend to have been bitten, and to cure themselves by the use of snake-stones, generally bits of charred bone, which they sell to the credulous.

There is much noise but little quarrelling in the bazaars, and the native policemen, in their blue serge tunics and trousers and red forage-caps, have little trouble in keeping order.

Continue to: