72. The Great Intestine

Description

This section is from the book "Animal Physiology: The Structure And Functions Of The Human Body", by John Cleland. Also available from Amazon: Animal Physiology, the Structure and Functions of the Human Body.

72. The Great Intestine

The Great Intestine has a smooth mucous membrane, with tubular follicles like those of the small intestine, but apparently having a different secretion. The details of the processes which take place in this part of the alimentary tube are but little understood. The bulk of the faeces consists of matters which have resisted all digestive processes, and always contains starch grains, muscular fibre, and vegetable tissues, when these substances have formed part of the diet.

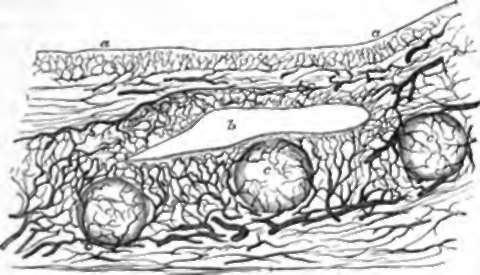

Fig. 58. Section of an Injected Tonsil, a, a. Mucous membrane of fauces; b, a recess; c, c, c, closed follicles.

73. Before leaving the consideration of the alimentary tube, a set of structures of obscure function, found in every part of it, may be mentioned, namely, the closed follicles. These are bodies the size of small millet grains, imbedded in the mucous membrane, and containing corpuscular matter and loops of capillary blood-vessels. A number of such structures, grouped round recesses of the mucous membrane of the fauces, constitute the tonsils (p. 88); they are also numerously scattered in the pharynx, and are called lenticular glands in the stomach. In the ileum they are gathered in elongated and rounded groups about half an inch broad, called Peyer's patches, or agminated glands; and in the great intestine they are very plentifully scattered all over, and called solitary glands. In recent years they have been very generally supposed to be connected with the absorbent system; but there is no sufficient proof that their function is not secretory, although their structure differs from that of secreting glands. Peyer's patches are interesting as being the seat of a deposit in typhoid fever, and subject to ulceration in that disease.

Fig. 59. Two Peter's Patuhes, natural size.

Continue to:

- prev: 70. The Action Of The Fluid Secreted By The Lieberkuhnian Follicles

- Table of Contents

- next: Chapter VIII. The Blood