Sadism And Masochism

Description

This section is from the book "Human Sexuality", by J. Richardson Parke. Also available from Amazon: Human Sexuality.

Sadism And Masochism

The impulse to inflict pain, on the part of the male, and to suffer it, on the part of the female, as an element in the expression of love, reduces courtship, as Colin Scott well remarks, to little more than "a refined and delicate form of combat," in which the male finds pleasure in the consciousness of power, and the female in submission to suffering as a part of the passion which that power excites.

Theories Of Marro And Of Schäfer

Marro has thought that there may be a sort of transference of emotion, in which the impulse of violence against the rival is turned, more or less unconsciously, against the beloved object; while Schafer is inclined to regard the impulse as atavistic,' battle and murder being so predominant an instinct, among the males of both animals and primitive man, that it is impossible not to see a close connection between them and innate male sexuality.

As Darwin, Spencer, MacLennan and other investigators have clearly pointed out, marriage by capture is not only so closely identified with the history of all early peoples, but modern courtship itself so largely dominated by the factor of physical force, that Marro's theory, as illustrated, for instance, in the biting of a mare by a stallion, during copulation, seems a fairly plausible one; the question of atavism not seriously assailing it, since one may be, and very probablv is, in rational correlation with the other.

Whatever its cause, the psychological fact admits of no disproof that the very highest degree of sexual enjoyment is frequently, if not always, found in connection with more or less violence on one side, and resistance on the other.

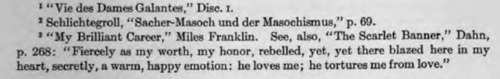

Brantome mentions a lady who confessed that she liked to be "half forced" by her husband;1 and everyone knows that the woman who resists is always more prized by men than she who yields too willingly. Among the Slavs the wife feels hurt if she is not occasionally beaten by her husband, treating such violence, according to Paullinus, as a mark of love.1

It is doubtful if the institution of the whipping-post for wife-beaters would be long sustained in any community, indeed, if women themselves were permitted to vote on it; and of the ho3t of poor, bruised, beaten and blackened female wretches, victims of man's brutality, who line up daily in our police courts, few will ever be found figuring in divorce cases.

I once told a woman who had been beaten by her husband that the latter was a brute, and received for my kindly effort at sympathy the snapping retort—"you mind your own business!" which I immediately proceeded to do. Acting on the old Russian proverb, possibly, that "a dear one's blows never hurt long," these poor souls actually love their stripes and slavery; and whatever the class in society, however the "advanced woman" may declaim against it, there is just sufficient of the primitive savage in all women to make them associate manly perfection with physical strength, and to look with a very lenient eye upon the violences of a true lover, provided he be one.

In a recent popular novel,1 the heroine, a young Australian lady, is represented as striking her lover with a whip for attempting to kiss her; but when he seizes her in return, with no very gentle grip, she realizes for the first time that he truly loves her. "I laughed a little joyous laugh," she remarks, "when on disrobing for the night I discovered on my white shoulders many black and blue marks. It had been a very happy day for nie."

Continue to:

- prev: Chapter Seven. Perversion Of The Sexual Impulse

- Table of Contents

- next: Probable Causation Of The Phenomena

Tags

sexuality, reporduction, genitals, love, female, humans, passion