Motion Of The Atmospheee

Description

This section is from the book "Trees And Tree-Planting", by James S. Brisbin. Also available from Amazon: Trees and Tree Planting.

Motion Of The Atmospheee

There is a marked contrast in the motion of a liquid like water, and an elastic, gaseous fluid like air. If we place an impediment in a creek the water immediately flows around the impediment, and will not flow over it as long as a clear way can be found to either the right or the left. But the air not only moves around on either side, but piles up in front of whatever checks its course and rolls over the top of the impediment as readily as it passes around. Thus a grove of timber or a thin shelter-belt effectually checks the motion of the wind.

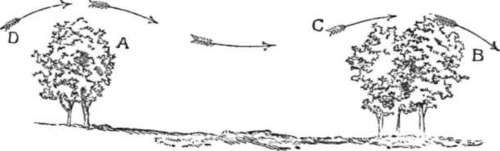

The wind rises over the trees, as indicated by the arrows in the figure, and, instead of falling like water to the ground, it flows on, as shown, and does not reach the original level until it has gone a distance of eleven times the height of the wind-breaks. There will be a quiet atmosphere immediately about the trees, but to eleven times the height of the shelter-belt, and even in the teeth of the wind at D, there will be a quiet atmosphere. It is well known that while the wind may sweep with fearful velocity over a forest and powerfully agitate the tops of trees, the motion is comparatively slight within the forest; the same is true of a succession of shelter-belts. The wind will sweep with great force over the trees at C, while all below remains quiet. The extent of these quiet spaces, A and B, will of course depend upon the height of the shelter-belts. Any one who will take the trouble can test the correctness of these views for himself.

We expect that the most important and positive results will follow a well-devised system of protection. It would exert a controlling influence over all farm operations. A judicious system of protection would be attended with the most beneficent results, while under certain other conditions it might be attended with disaster.

Continue to:

- prev: Chapter XII. Shelter-Belts

- Table of Contents

- next: Facts