At Monastery Gates. Part 3

Description

This section is from the book "The Life Of Francis Thompson", by Everard Meynell. Also available from Amazon: The life of Francis Thompson.

At Monastery Gates. Part 3

2 Dr. Henry Head, F.R.S.

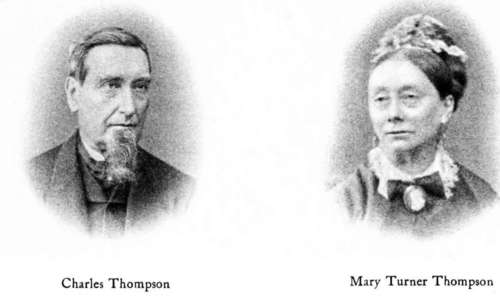

Francis Thompson's Parents.

" Need I say that I am truly touched to hear that Thompson should have thought my modest appreciation of his work as anything more than the most natural thing in the world ? I only met him three times, each time in the company of my friend Head,2 who shared my admiration. Our meeting came about in an absurd enough wise. A ghost (possibly you have heard, or not heard, of my taste for these creatures) was reported active in the neighbourhood of Pantasaph, on my brother's place in Wales. My own inclination supplied the motive, and an idle week of Head's the occasion, of a visit there, and we camped a few nights in a derelict mansion, rejoicing in the appropriately ominous name of Pickpocket Hall, in hopes of interviewing the spectre. Needless to say, we failed. But we got the story of the Irish monk; also the story of the practical nun, who scented buried treasure which she hoped to unearth to the profit of her community; and of the oldest inhabitant; and, finally, of the Poet. The people at the monastery had told us that Thompson had been a witness, and we decided on a call; and at about five one evening made our way to the tiny cottage where he lodged, and asked for him. He was still in bed. We returned at 6.30. He was still in bed. So we concocted a letter, suitable, as we imagined, to the person who had written Thompson's poems, not quite English, somewhat elided, and as inverted as we could manage, ending with an invitation to breakfast at 9.30 that night and a conference with our hobgoblin. And somewhat pleased with our effort, we retired to our haunted mansion and awaited events. At 9.30 he came and breakfasted while we supped. We said at once to one another: ' This is not the man to whom we wrote that letter.' For, instead of parables in polysyllables and a riot of imagery, we found simplicity and modesty and a manner which would have been almost commonplace if it had not been so sincere. But the charm and interest of his talk grew with the night, and it was already dawn when, the ghost long since forgotten, we escorted him back across the snow to his untimely lunch. He told us, I remember, of his poetical development, and of how, until recently, he had fancied that the end of poetry was reached in the stringing together of ingenious images, an art in which, he somewhat naively confessed, he knew himself to excel; but that now he knew it should reach further, and he hoped for an improvement in his future work. New Poems was subsequent to this meeting. It was only in his account of the ghost, which had ' charged his body like a battery so that he felt thunderstorms in his hair,' that the imaginary individual to whom we had addressed our letter revealed himself.

" He dined with us twice afterwards, the second time appearing an hour late, with his head tied up in an appalling bandage, the result of having been knocked down by a hansom, so that I took his arrival under the circumstances as a compliment second only to your own kind letter. For years I haven't seen him. A letter, to ask him if he would renew acquaintance, has several times trembled on the tip of my pen; but I was told he had become inaccessible, and it never went, and now I am very sorry."

Something of the Pantasaph ghost got into verse, which I take from a note-book :-

More creatures lackey man

Than he has note of: through the ways of air

Angels go here and there

About his businesses : we tread the floor

Of a whole sea of spirits : evermore

Oozy with spirits ebbs the air and flows

Round us, and no man knows.

Spirits drift upon the populous breeze

And throng the twinkling leaves that twirl on summer trees.

In notes headed "Varia on Magic" he quotes the

Anatomy of Melancholy:-

"The air is not so full of flies in summer, as it is at all times of invisible devils: this Paracelsus stiffly maintains."

F. T. wrote to A. M. after the meeting :-

" Is it true that you are going to collect your contributions ,to the papers during the last few years ? I sincerely hope so. . . . There was a Dr. Head, a member of the Savile Club, over here last autumn with Everard Feilding, who spoke with great enthusiasm of your " Auto-lycus." He quoted a bit relating, I think, to Angelica Kaufmann,1 who spent a large number of years in ' taking the plainness off paper.' The phrase delighted him, as it did me who had not seen it. ... I passed a pleasant night with the two. We were sleeping in a haunted house to interview the ghost; but as he was a racing-man, he probably found our conversation too literary to put off his incognito."

1 It was not Angelica, but Mrs. Delany.

The friars helped him to another companion, Coventry Patmore, who as a member of the Third Order, went in 1894 to stay at Pantasaph. There Father Anselm, a bachelor of St. Francis, with the Lady Poverty first among his feminine acquaintance, could meet the greatest of English love-poets upon equal terms. It was to Fr. Anselm that Francis had lent Patmore's Religio Poeta before trusting himself to review it, and it was by the same friar that he was helped to appreciate Patmore's trustworthiness as a witness to divine truths. By none save by a priest of the Church would the poet of the Church have been satisfied that he might lawfully accept, or attempt to accept, teaching that had once seemed to him inimical to orthodoxy. Religio Poetce, at first a stumbling-block, was to become the corner-stone of his later poetry. Two years before (in August 1892) he had said there were two points in C. P.'s teaching-as to the nature of the union between God and man in this world and the next, and the definition of the constitution of Heaven-that he refused absolutely to accept. He went specially to Crawley in 1892 to consult Fr. Cuthbert on these points. And he had at first only unwillingly admitted Patmore's power over him. To a passage of St. John (chap, xxi.) he adds a note that reveals his mood:-

Continue to: