Lampreys And Lamperns

Description

This section is from the book "Sea Fishing", by John Bickerdyke. Also available from Amazon: Sea Fishing.

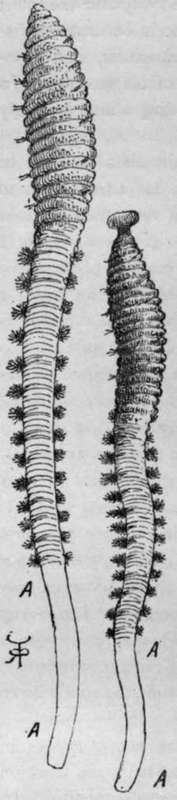

Lampreys And Lamperns

Lampreys are first-rate whiffing baits, equally as good as small eels, and should be used in exactly the same manner. They have much the appearance of eels, but a very curious sucking apparatus takes the place of a mouth. There are several varieties of these creatures, some of which are found in the sea, while others appear to live permanently in fresh water. They are, or used to be, used alive on the long lines as baits for turbot, that fish being particularly partial to them. I have caught large numbers of the lesser lamprey in early spring, when they have been spawning on the shallows of a trout stream.

Limpets

These humble little shell fish, which appear to pass aimless existences adhering to rocks, are a good deal used for baits in places where mussels are scarce or wanting. They are highly esteemed in the Orkneys, and are deemed most serviceable if scalded out of the shell, but not boiled. I confess I never had much respect for these shell fish until I learnt from a scientific work that they were cyclobranchiate gasteropodous molluscs of the genus Patella. The limpet is cyclobranchiate because his gills or branchiae form a fringe round his body between the edge of the body and the foot ; and he belongs to the order of gasteropods because his distinguishing characteristic is the broad, muscular, and disclike foot which is attached to the surface of his stomach. In fact, he walks on his stomach, a proceeding which is rarely seen.

If the rock be soft, the limpet digs himself a little pit in which he rests, making his way therefrom for a few inches to feed on various kinds of seaweed. As a rule, these curious creatures do not move except when covered by water ; but I once saw one taking an airing, and a very curious performance it was. The shell was raised about an eighth of an inch ; a tiny feeler peeped out, waved to and fro and felt about as if to ascertain if the next twenty-fifth of an inch of rock was suitable for progression. After the limpet was satisfied on this important point, the edges of its body began to work slowly all round the shell, and a step forward was made. And that was the locomotion of a gasteropod, with whom time was apparently no object. When the limpet has made up its mind to stick in one place, it shows great determination to that end. It has been recently calculated that it requires a force of about 60 lbs., or upwards of 2,000 times its own weight without its shell, to pull it away from the rock. It is, however, easy enough to dislodge these strong men among shell fish if you know the right way. Take them unawares and give them a sharp tap, and they tumble down as if shot ; or gently insinuate a knife under the shell before they have time to crouch down on to the rock.

Limpets are a good deal eaten by the poorer classes in some parts of Ireland and Scotland, and, as baits, are used on the haddock lines when, as I have said, mussels or better baits are not obtainable. The soft part of a limpet is considered a very fair bait for sea bream ; by reason of its softness it should be cut out and placed in the air to dry for an hour or two before being used. A whole limpet threaded up the shank of a hook, followed by a lugworm, makes a very killing bait for codfish. It is illustrated in Chapter XIII.

Lugworm.

Continue to:

- prev: Herring

- Table of Contents

- next: Lugworms

Tags

fishing, hooks, bait, fishermen, spanish mackerel, mackerel fishing