Chapter XVIII. On Guard

Description

This section is from the book "The Boy Scouts of Woodcraft Camp", by Thornton W. Burgess. Also available from Amazon: The Boy Scouts Of Woodcraft Camp.

Chapter XVIII. On Guard

On the bald top of Old Scraggy stood a slender figure in khaki. The broad-brimmed regulation Scout hat was tilted back, revealing a sun-browned face which was good to see. The eyes were clear and steady. The mouth might have been called weak but for a certain set of the jaw and a slight compression of the thin lips which denoted a latent force of will which would one day develop into power. It was, withal, a pleasant face, a face in which character was written, a face which denoted purpose and determination.

The boy raised a pair of field-glasses to his eyes and swept the wonderful panorama of forest and lake that unfolded below him on every side. Like mighty billows of living green the mountains rolled away to fade into the smoke haze that stretched along the horizon. The smell of smoke was in the air. Over beyond Mt. Seward hung a huge cloud of dirty white against which rose great volumes of black, shading down to dingy sickening yellowish tinge at the horizon. Through his glasses the boy could see this shot through here and there with angry red. There was something indescribably sinister and menacing in it, even to his inexperienced eyes. It was like a huge beast snarling and showing its teeth as it devoured its prey. On the back side of the Camel's Hump another fire was raging. But neither of these seriously threatened Woodcraft Camp, for a barrier of lakes lay between.

" I'm glad they're no nearer," muttered the watcher half aloud. He swung his glasses around to the camp five miles away by the trail, though not more than three and a half in an air line, and his face softened as he studied the familiar scene. There was a song in his heart and the burden of it was, " They have got some use for me! They have got some use for me ! They have got some use for me ! " It was Hal Harrison.

There had been a wonderful change in the boy in the few weeks since his meeting with Walter Upton at Speckled Brook. It had been a hard fight, a bitter fight; sometimes, it seemed to him, a losing fight. But he had triumphed in the end. He had " made good " with his fellow Scouts. He had friends, a lot of them. With only one or two was he what might be called intimate, but on every side were friendly greetings. From being an outcast he had become a factor in the camp life. He was counted in as a matter of course in all the fun and frolic. He had done nothing " big " to win this regard. It was simply the result of meeting his fellows on their own ground and doing his share in the trivial things that go to make up daily life.

He was thinking of this now and his changed attitude toward life, toward his fellow men. In a dim way he realized that a revolution had been worked within himself, and that his present status in the little democracy down there on the edge of the lake was due, not so much to a change in the general feeling of his comrades toward him, but in his own feeling toward them. His present position had always been his, but he had refused to take it.

Somehow money, which had been his sole standard whereby to judge his fellows, bad dropped from his thought utterly as he strove to measure up his comrades. It had even become hateful to him as he gradually realized how less than nothing it is in the final summing up of true worth, of character and manhood. And with this knowledge all his old arrogance had fallen from him like a false garment, and in its place had developed a humility that cleared his vision and enabled him to see things in their true relations.

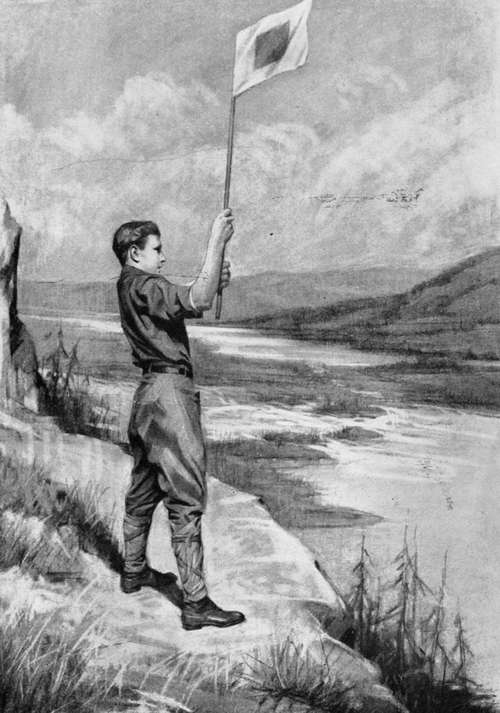

The Boys Were Drilled In Wigwag Signalling

" My, what a cad I was when I hit Woodcraft, and how little I realized what the Scout's oath means ! " he murmured. " The fellows have been awfully white to me. If— if I could only do something to show 'em that I appreciate it, could only really and truly 1 make good ' somehow. Seems to me this smoke is getting thicker."

He turned once more toward Seward. The wind was freshening and the smoke driven before it was settling in a great pall that spread and gradually blotted out mountain after mountain. The blue haze thickened in the valleys. When he turned again toward Woodcraft it had become a blur. The sun, which had poured a flood of brilliant light from a cloudless sky, had become overcast and now-burned an angry red ball through a murky atmosphere. His throat smarted from the acrid smoke. There was a strange silence, as if the great wilderness held its breath in hushed awe in the face of some dread catastrophe.

Hal was on guard. It was Dr. Merriam's policy to always maintain a watch on the top of Old Scraggy during dry weather that any fire which should start in the neighborhood might be detected in its incipient stages and a warning be flashed to camp. The boys were drilled in wig-wag signaling, and in the use of the heliograph, the former for use on a dull day and the latter on a bright day, the top of Old Scraggy being clearly visible from camp, so that with glasses the wig-wag signals could be read easily. At daybreak a watch was sent to the mountain station, while another went on duty at the camp to receive the signals. At noon both guards were relieved. Only the steadiest and most reliable boys were detailed for this duty. This was Hal's first assignment and, while he felt the responsibility, he had hit the Scraggy trail with a light heart, for he realized the compliment to his scout-craft. And was not this evidence that he was making good ?

The smoke thickened. The smart in his eyes and throat increased. Uneasily he paced the little platform that had been built on the highest point. Suddenly it seemed as if his heart stopped beating for just a second. Why did the smoke seem so much thicker down there to the east at the very foot of Scraggy itself? With trembling fingers he focussed the glasses. The smoke was rising at that point, not settling down ! Yes, he could not be mistaken, there was a nicker of red ! There was a fire on the eastern slope!

Continue to: