Highly Coloured Foliage Effects

Description

This section is from the book "What England Can Teach Us About Gardening", by Wilhelm Miller. Also available from Amazon: What England Can Teach Us About Gardening.

Highly Coloured Foliage Effects

There are some enthusiasts about hardy plants who make a fetich of the idea of hardiness. They see nothing objectionable in a lawn peppered with copper beech, purple plum, golden elder, and variegated weigela because the plants are hardy. But I can see no reason why hardy plants with gaudy foliage are any better than tender ones. Strangely enough, there are some fifty hardy plants now used in conventional bedding because they have purple or metallic foliage or something else to "frizzle the eyebrows," as Dean Hole used to say. The great lesson we should learn is that abnormally coloured foliage is too different to be used in any large way. The most objectionable bedding effects are those produced by such unnatural looking foliage as coleus, horseshoe geraniums, alternantheras, acalyphas, and such foreign-looking flowers as lantanas, and mesembryanthemums. Moreover, all violent contrasts and intricate patterns are in questionable taste.

I said that there was a sweeter and purer way of getting brilliant colour and a long season of bloom. It is by means of hardy flowers, such as ever-blooming pinks, tufted violets, forget-me-not, woolly chickweed, evening primroses, pyrethrums, bugles, stonecrops, and many others mentioned in Chapter XXIV. And if, for any reason, they will not do the required work, we can go back to the loveliest of annual flowers for bedding purposes, such as heliotrope, verbena, stocks, nasturtiums, catchfly, and scarlet sage.

I would not rule tropical plants entirely out of Northern gardens for summer effect for I would not be extreme in anything, but we lean on these plants altogether too much. We should make them incidental, as England does. Until the desire for showiness gives way to the desire for appropriateness our gardens will lack charm. And until we stop looking to Europe for material and discover our own hardy plants we shall only make poor copies of Old-World gardens instead of achieving a national style of our own.

Since writing this chapter a notable book has been published — "Spring Flowers at Belvoir Castle," by W. H. Divers. Although devoted only to spring bedding, it shows how to carry out a great many of the ideas I have suggested, giving invaluable details about propagation and cultivation. For instance, Mr. Divers explains how to give the beds a green appearance all the winter. Also he gives a good list of material and an admirable classification according to methods of propagation. For example, Class I contains "plants raised from division of the stock in March," Class III contains " plants raised from seeds sown in the year previous to flowering with the month of sowing," etc.

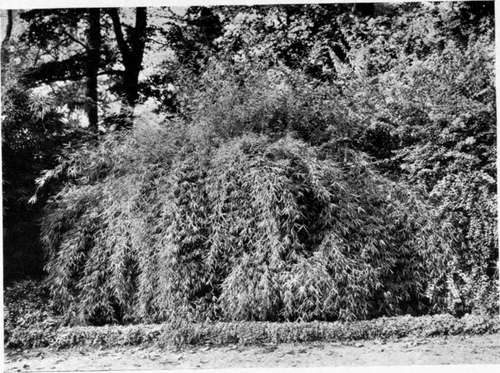

THE LADY BAMBOO (Arundinaria nitida), CONSIDERED BY MR. MITFORD THE DAINTEST OF THE HARDY BAMBOOS. See pages 174, 328.

THE NOBLEST OF HARDY EVERGREEN BAMBOOS, HAVING LEAVES TEN TO FIFTEEN INCHES LONG AND THREE INCHES WIDE. GROWS FIVE FEET HIGH. PROBABLY BAMBUSA PALMATA. See page 174.

Continue to:

- prev: Other "Feminine" Effects

- Table of Contents

- next: Chapter XXVI. Lessons From English Cottage Gardens

Tags

garden, flowers, plants, England, effects, foliage, gardening