Chapter XXI. English Effects With Long Lived Bulbs

Description

This section is from the book "What England Can Teach Us About Gardening", by Wilhelm Miller. Also available from Amazon: What England Can Teach Us About Gardening.

Chapter XXI. English Effects With Long Lived Bulbs

The cheapest way of growing flowers by the million in wood, meadow, and orchard, where they will multiply without care and create visions of supreme beauty.

BY FAR the most important lesson England has to teach us about bulbs is that they furnish the cheapest way of growing flowers by the million in wood, meadow, and orchard, where they will look and act like wild flowers, multiplying without care and finally creating visions of supreme beauty.

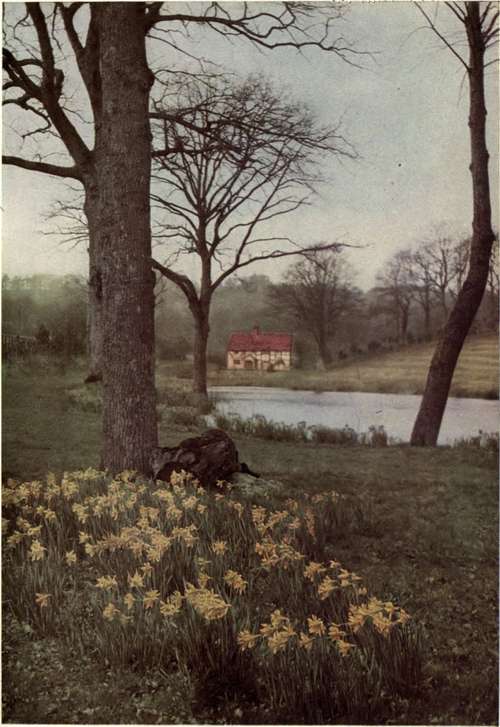

For example, take the two daffodil pictures on plates 86 and 87. You could see these yellow flowers tossing " their heads in sprightly dance," on your own grassy land, without any sign of the spade or handiwork of man! It is hard to realize that daffodils live as long as apple trees and are surer to bear a crop every year. Yet there is a field near Trenton, N. J., where they have been blooming every April for one hundred years without care!

From the economic point of view wild gardening is absolutely justified, because it is the cheapest form of gardening. These daffodils, for instance, cost one or two cents a bulb. They do not interfere with a hay crop in meadow or orchard. By the middle of June, when you are ready to cut hay, the leaves of the daffodils will have ripened, turned yellow, and fallen flat upon the ground.

The same is true of all other spring-blooming bulbs that have strength enough to force their way through the turf year after year. They do not seriously reduce the hay crop, and cutting the hay does not harm them at all.

But can foreign flowers ever look like wild flowers in America? Certainly. The poet's narcissuses not native to England, but who knows or cares, save the botanist? The great thing for England is that it multiplies of its own accord, producing myriads of fragrant, starry white blossoms in May, and bending before the breeze with as much wild grace as any native flower you could name.

So, too, there are dozens of beautiful foreign plants that have run wild in America with little or no help from man, e. g., the buttercup, sweet rocket, Johnny-jump-up, spiked loosestrife, wall pepper, barberry, and marsh mallow. It comes as a surprise to us to learn that these are natives, not of America but of Europe.

The underlying principle is this: Any flower will look wild if it can hold its own or multiply without care in the long grass or in the woods. The costliest flowers in the world will not look wild if they last only a season or two, or if there is any evidence of the spade or watering pot.

England is the home of wild gardening, and we must go there to see how to make the most ravishing pictures with bulbs. I cannot see that the English have any great climatic advantage over us in respect to bulbs. They can grow a few kinds with which we usually fail, e. g., the florist's anemone and ranunculus, the winter aconite, European cyclamen, Grecian wind-flower, and Apennine anemone. On the other hand, we can grow gladioli better than they. Their early spring gives them twice as long a season for daffodils as New England has, for they have many varieties that will bloom in March. They have a commercial advantage in being able to buy bulbs very cheaply, while we have a big duty to pay.

88. DAFFODILS PLANTED IN A NATURAL AND PICTURESQUE WAY. NOT IN SOLID MASSES AS IN A NURSERY, NOR YET SCATTERED AIMLESSLY. UPPER POOL, GRAVETYE.

On the other hand, America ought to excel England in wild gardening because we have more land and wealth and a greater variety of climate, soil, and plants. Eventually we must grow our own bulbs so that they will blossom in every door yard in the land.

The best English effects with bulbs are easy to reproduce in America, because all we have to do, in most cases, is to plant the bulbs in good soil this fall and they will bloom next spring. In other departments of gardening it is necessary for us to use many substitutes or equivalents. In the case of bulbs we can generally use the identical varieties grown in England.

Continue to:

Tags

garden, flowers, plants, England, effects, foliage, gardening